The Slave Trade

Jack Weinstein, Ashley Chun, and Rachel Schiffer

From the sixteenth to the nineteenth century, the transatlantic slave trade transported approximately 10.7 million enslaved people from Africa to colonies in the Americas (“Estimates”). Also known as the “triangular trade,” the process moved goods and people between three continents—Africa, America, and Europe. European traders brought goods like wine, guns, and ammunition to African trading posts, where they exchanged them for enslaved people. The traders then brought the enslaved individuals across the Atlantic on the infamous “Middle Passage,” where 20% of the Africans on board died (“Life on board slave ships”). Finally, the traders exchanged enslaved people for American goods like cotton, tobacco, and sugar, which they then brought back to Europe. Over the course of four centuries, four million enslaved people were transported to Brazil, four million to Dutch American colonies, and two million to the British Caribbean. Only 388,000 (3.6%) of enslaved people taken from Africa landed in mainland North America (“Estimates”).

While the first British slave trading voyage was led by John Hawkins in 1562, the British slave trade developed more fully in the 1640s and revolved around sugarcane. England went on to become one of the biggest slave trading nations in the world. The National Archives estimates that the empire transported about “3.1 million Africans—of whom [only] 2.7 million arrived” (“Britain and the Slave Trade”). In the 1790s, attempts were made to put an end to the slave trade, and growing disapproval eventually resulted in the Slave Trade Act of 1807, which officially outlawed the trading of enslaved people within the British Empire (“British Transatlantic Slave Trade records”).

The first boat carrying enslaved Africans to what is now the United States arrived in the Virginia colony in 1619, shortly after Jamestown was established (“A History of Slavery in the United States”). After the American Revolution, the maintenance of slavery was written into the United States Constitution through the Fugitive Slave Clause, the three-fifths compromise, and a clause stipulating that the government could not end slavery for at least twenty years (“The Annenberg Guide to the United States Constitution”). In 1808, Congress banned the import of foreign enslaved people, while specifying that enslaved people could still be bought and sold within the United States. However, the last ship carrying enslaved Africans to the United States arrived in Alabama in 1859, fifty-one years after the import of enslaved people had been prohibited (“A History of Slavery in the United States”).

~~~~~

Africa: Being an Accurate Description of the Regions of Ægypt, Barbary, Lybia, and Billedulgerid, the Land of Negroes, Guinee, Æthiopia and the Abyssines…

John Ogilby

London: Printed by T. Johnson for the author, 1670

Ashley Chun

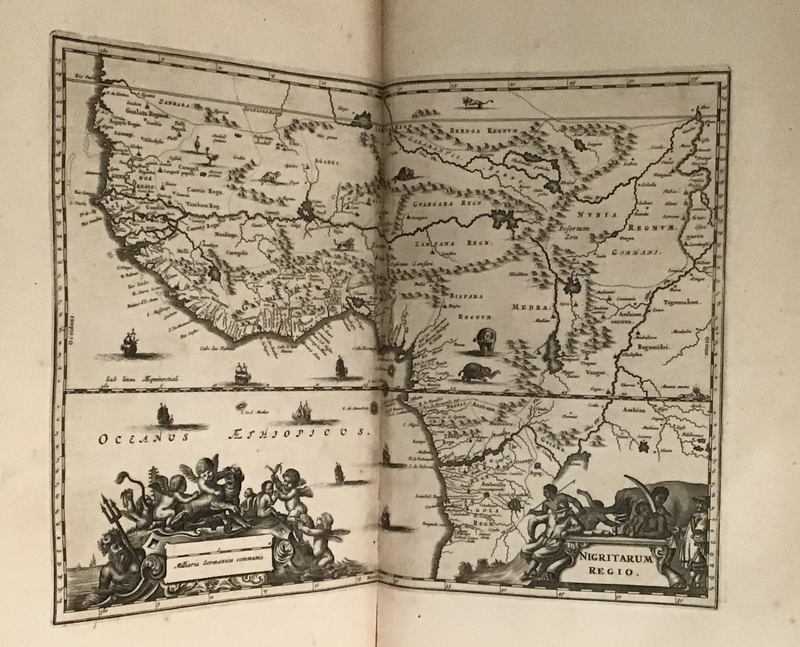

Africa, a large, encyclopedic book, details the wonders of the African continent. The book includes entries on Africa’s geography, government systems, religions, and languages, interspersed with full-page maps, drawings, and diagrams. The liberal usage of hyperbole regarding Africa’s “exceedingly fruitful” land and “great number of ravenous beasts” suggests that Ogilby’s target audience would have never actually made the journey to Africa. Ogilby’s account of Africa resonates with Aphra Behn’s description of Africa in her novel Oroonoko. In both accounts, the authors describe Africa’s land and beasts as rich but unruly, present Africans using racialized and sexualized language, and refer to African society as uncivilized.

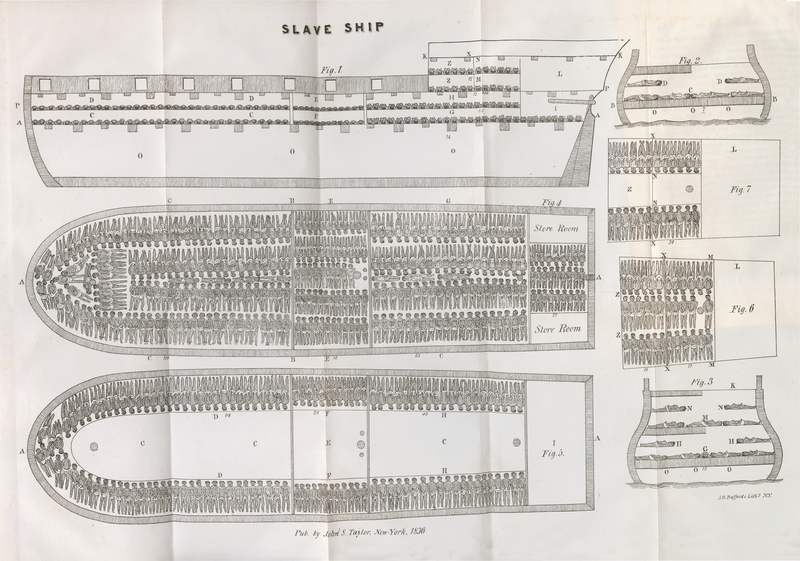

A fold-out diagram of a slaving ship found in Thomas Clarkson's The History of the Rise, Progress, and Accomplishment of the Abolition (1836). A version of the much older "Brookes diagram" from 1787.

"The History of the Rise, Progress, and Accomplishment of the Abolition of the African Slave-Trade, by the British Parliament”

From The Cabinet of Freedom, 1836

Thomas Clarkson

William Moore

This essay by British abolitionist Thomas Clarkson seeks to provide readers with a complete history of slavery, containing both “facts” and moral judgements condemning its “evils.” The most notable part of the text is a fold-out diagram of a slaving ship, on display here, a version of the much older “Brookes diagram” from 1787. Clarkson’s essay first appeared in print a year after the abolition of the British slave trade in 1807. This 1836 edition was published in New York as part of a series called The Cabinet of Freedom, because the “print seemed to make an instantaneous impression of horror upon all who saw it,” facilitating its “wide circulation” by abolitionists.

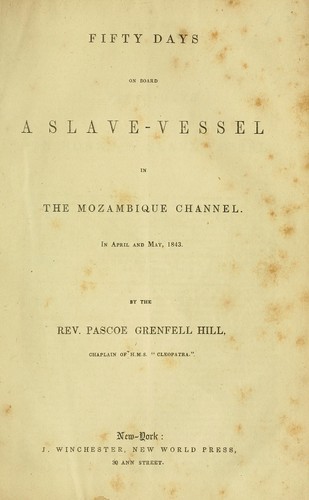

Fifty Days on Board a Slave-Vessel in the Mozambique Channel, in April and May, 1843

Pascoe Grenfell Hill

New York: J. Winchester, 1843

William Moore

Reverend Hill relates his experiences as the chaplain of the H.M.S. “Cleopatra,” an anti-slaver patrol ship stationed in the Mozambique Channel in 1843. The bulk of the pamphlet centers around the capture of the “Progresso,” carrying a cargo of 447 enslaved persons, who endured such wretched conditions that only 222 remained alive by the time the crew disembarked. Hill is clearly horrified by the slave trade and slavery more broadly, but his record still contains substantial racism: he mentions how the crew often refered to a rescued person as “it” and “ought to feel more sympathy for the[m].”

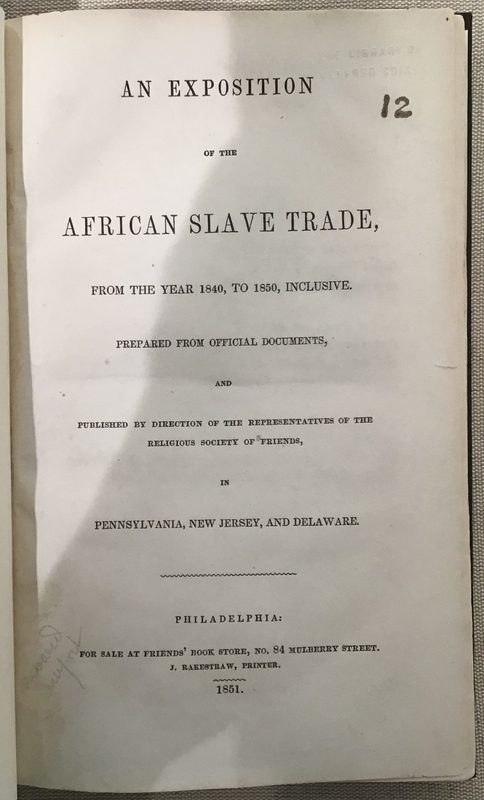

An Exposition of the African Slave Trade

Philadelphia: Friends' book store, 1851

Ashley Chun

This small, light volume offers a history and condemnation of the African slave trade. It outlines how the slave trade grew and adapted to changing legislation in countries such as the United States, Brazil, Spain, the United Kingdom, and Portugal. While the authors praise the United States for the steps it took “as early as 1794,” they urge the American people to do more. Noting that God would not approve of “the enslavement of his creations,” the text places a moral responsibility on Americans to condemn the slave trade. It further encourages Americans to look down on Brazil and Spain, Catholic powers—as opposed to the Protestant United States—which were notoriously large players in the African slave trade.