The 19th Century: Romanticism, Satire, and Somewhere In Between

While Don Quixote may have mocked mythological Spanish lineages in 1615, by 1815, it had developed a mythological Spanish lineage of its own. In the 19th century, interpretations of Cervantes’ novel blended Spanish nationalism with the Romantic movement, a movement in arts and literature that emphasized qualities such as, in Wordsworth's words, “the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings” (qtd. in Abrams and Harpham 2) and “the faculty of imagination” (Abrams and Harpham 3). Many Spanish Romantic critics of the novel saw it as a continuation of the medieval “ballad-tradition” and viewed Spain “as the country where things medieval were deemed to have most prospered” (Close 56). In the imagined “reality” of these literary critiques and some Spanish politicians, the high chivalric ideals of el ingenioso hidalgo de la mancha were viewed with admiration rather than comic spite as they reflected the grandeur of a long-existing Spanish nationalism.

The more serious romantic interpretation of Don Quixote did not limit itself to the patriotic writings of Spaniards. In Victorian England, writers and scholars praised Don Quixote’s heroic imagination even if his attempts at heroism met with unfortunate results. As Anthony Close writes, 19th-century Romantics changed the novel from “a satire upon Enthusiasm” into a novel in which “Enthusiasm [had] become the quintessence of the spiritual” and the titular character into the “universal type of the idealist” (57). The Romantic movement praised passion and sentimentality, and correspondingly it reimagined Cervantes’ character into one laudable for his tragic idealism.

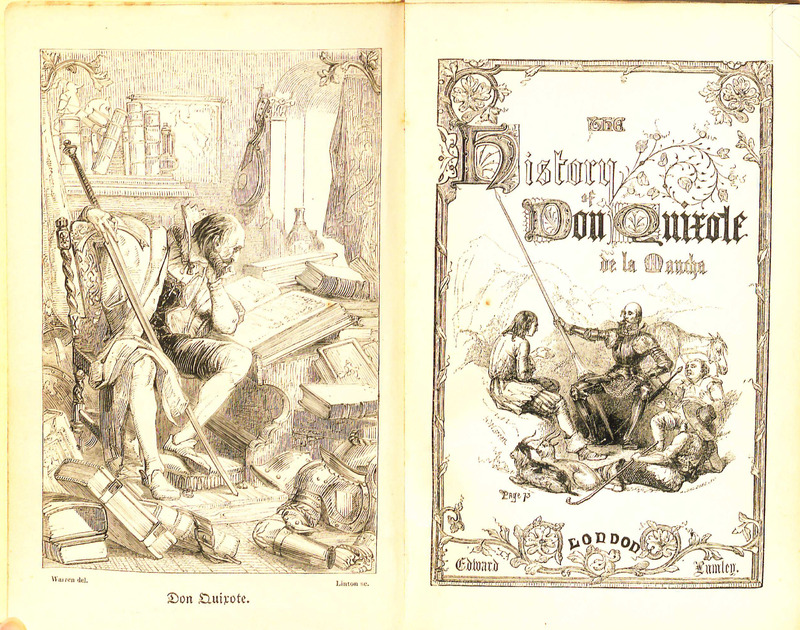

The engraving from this 1847 English edition of Don Quixote by Stephen Alonzo Schoff depicts a more elegant and regal knight-errant. Far from simply satirizing the fantastical imaginings brought on by his books of chivalry, the image of Don Quixote reading chivalric tales conjures up the viewer’s sympathy and admiration. In images like this, the Romantics’ conception of an admirably passionate Don Quixote shaped the visual reality of the published text.

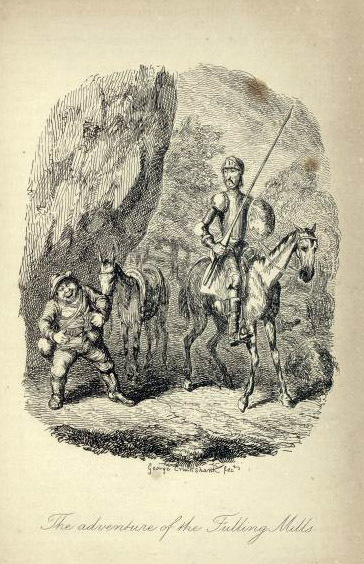

Although prevalent, the Romantic approach did not dominate all imaginings of Don Quixote in the 19th century. While Schoff’s engravings deliberately create a regal and elegant knight-errant, the images created by English satirist George Cruikshank deliberately portray the knight-errant as grotesquely humorous. In ““Don Quixote” as a Funny Book” , P. E. Russell argues that Cervantes intentionally crafted a comical titular character by drawing on ideas about madness intrinsically humorous to his 17th century audience. One of Cruikshank’s images of Don Quixote battling an imaginary foe takes this intentionality of humor to a visual level. The face of the sword-wielding madman of La Mancha appears senile and inept while Sancho Panza looks on with buffoon-like surprise. As a satirist, Cruickshank’s interpretive “reality” of Don Quixote was a comedic one, and he used his visual reality of his illustration to create a Don Quixote close to his imagining.

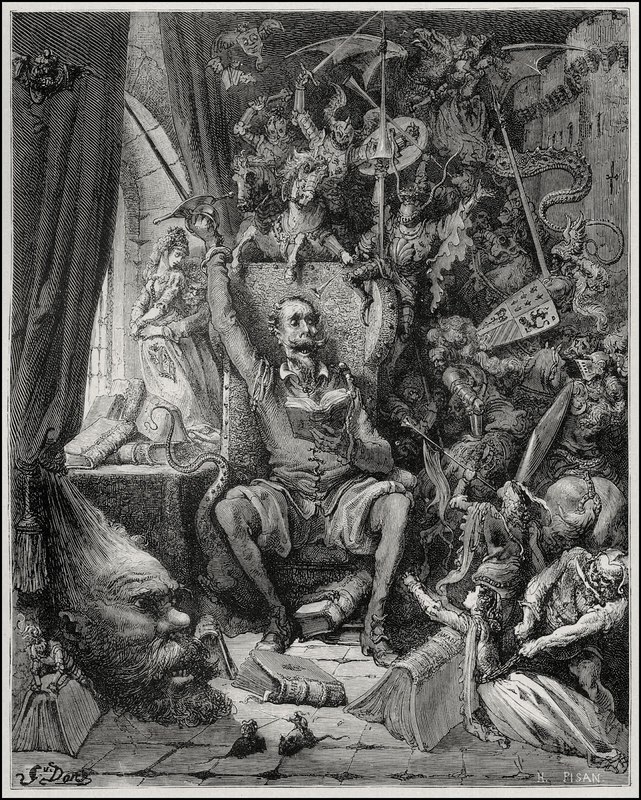

When Gustave Dore illustrated el ingenioso hidalgo de la mancha and his squire for an 1860 French edition of Don Quixote, he created images that would become the definitive versions of these characters. Dore’s images of the knight-errant are comical, but not grotesquely comical like Cruickshank’s. Dore portrays the titular character in a more sympathetic light; as a light-hearted fool rather than a ridiculous madman. The image of Don Quixote’s imaginings of chivalry brought to life that appears within the first few pages of our English Dore edition makes the viewer laugh at its humorous figures yet still experience a sense of wonder with its large proportions. Anthony Close calls Dore’s ima Don Quixote “a synthesis of contradictory elements” including “saintliness, chivalry, frenzy,” and “inept comicality” (54). The multifaceted aesthetic of Dore’s work lends itself easily to either a satirical or romantic imagining of Don Quixote. Perhaps, mirroring the malleability of Cervantes’ novel itself, Dore’s illustrations have endured by creating a physical visual reality conducive to multiple imagined “realities.”

Works Cited

Abrams and Harpham. A Glossary of Literary Terms. Eleventh Edition. Australia ; Cengage Learning, 2015. Print.

Close, A. J. The Romantic Approach to Don Quixote: A Critical History of the Romantic Tradition in Quixote Criticism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978. Print.

Russell, P.E. "Don Quixote as a Funny Book.” The Modern Language Review 64.2 (1969): 312–326. Web.