Historical Background

When Don Quixote wanted to become the great knight of La Mancha, “the first thing he did was to clean up some armor that had belonged to his ancestors and had for ages been lying forgotten in a corner, covered with rust and mildew” (Ormsby 27). When el ingenioso hidalgo de la mancha puts on antiquated armor, the physical reality of knights in early 17th-century Spain is contrasted with their imagined mythos of chivalric culture. Like Don Quixote’s armor, Spanish knights, or caballeros, had by 1605 become obsolete as gallant warriors. As Christian Spain slowed down its campaigns of conquest against Muslim lands, caballeros were more often found governing territory than wielding a lance. As William Childers explains in Transnational Cervantes (2006), the consolidation of territory reduced Spanish knights to “courtiers,” who “continued to exercise . . . an important prestige function” (30). These knights-turned-territorial-governors asserted their positions of power within the seventeenth-century Spanish nation by boasting of glorious, often embellished, lineages of chivalric service to the crown. Additionally, many members of the “petty nobility” attempted to gain hidalgo, or gentleman status, by also claiming records of chivalric military service (Childers 34). Like Don Quixote himself, early modern Spaniards were infatuated with the chivalric legends of the past despite the waning existence of actual knights in armor.

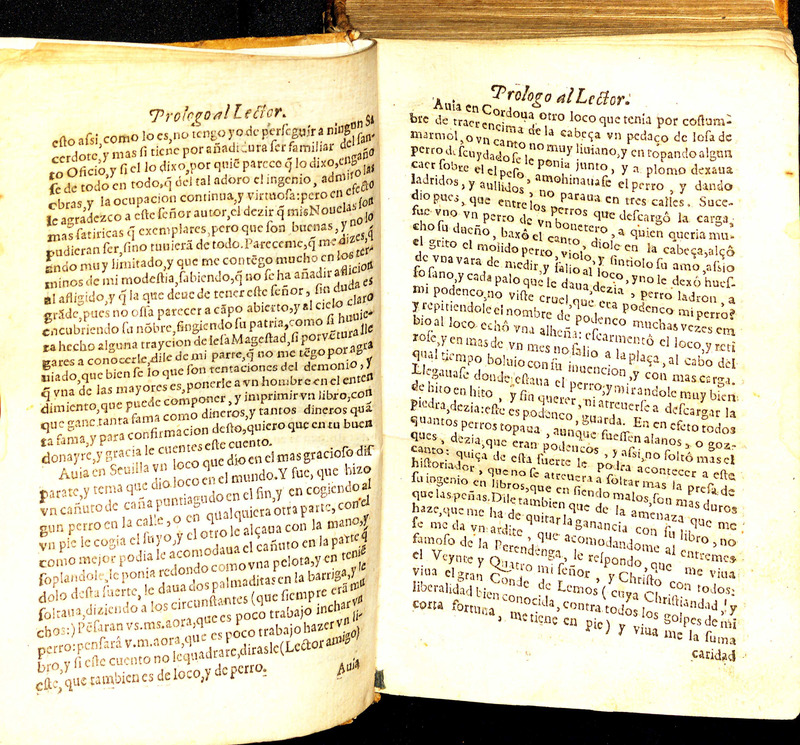

In Don Quixote, Cervantes draws attention to the ways in which the imagined “realities” of chivalric legends gained credibility in Spanish society and literature. Instead of indicating their fictitious components, books that contained chivalric legends presented themselves as historical accounts and referenced other well-known sources to add realism to the imagined “realities” they created. In the prólogo to Don Quixote, Cervantes complains to a friend that he does not have enough learned references for anyone to take his story seriously. His friend replies with a lengthy list of figures from the Bible and Antiquity, telling Cervantes, “no hay más sino que vos procuréis nombrar estos nombres, o tocar estas historias en la vuestra, que aquí he dicho, y dejadme a mí el cargo de poner las anotaciones y acotaciones” (12) “all you have to do is to manage to quote these names or refer to these stories I have mentioned, and leave it to me to insert the annotations and quotations” (Ormsby 12). The author also prefaces his story with sonnets and letters from fictitious persons of importance. Cervantes mimics both the archetypal tale of the chivalric knight with his tale of Don Quixote and the ways in which writers of chivalric tales would physically fill their books with many references to fabricate ethos. By filling the physical reality of his novel with a prólogo full of references to the Bible and antiquity and fictitious sonnets and letters, Cervantes invites his readers to read the work as a parody of the mythos of chivalric culture and books of chivalry.

However, not all readers read Don Quixote as a parody of books of chivalry, or as a parody of books of chivalry for the same reasons. What were some of the other imagined “realities” of Don Quixote for some of its other readers? How did these other readers interact with the physical reality of the text of Don Quixote to support their imagined reality?

Works Cited

Cervantes Saavedra, Miguel de. El Ingenioso Hidalgo: Don Quijote De Al Mancha. Buenos Aires: Espasa-Calpe Argentina, 1940. Print.

———. Don Quixote: The Ormsby Translation, Revised, Backgrounds and Sources, Criticism. Ed. Joseph R. Jones and Kenneth Douglas. Trans. John Ormsby. New York : W.W. Norton, 1981. Print.

Childers, William. Transnational Cervantes. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2006. Print.