Mythical Conceptions of Chivalry and Physical Circulation

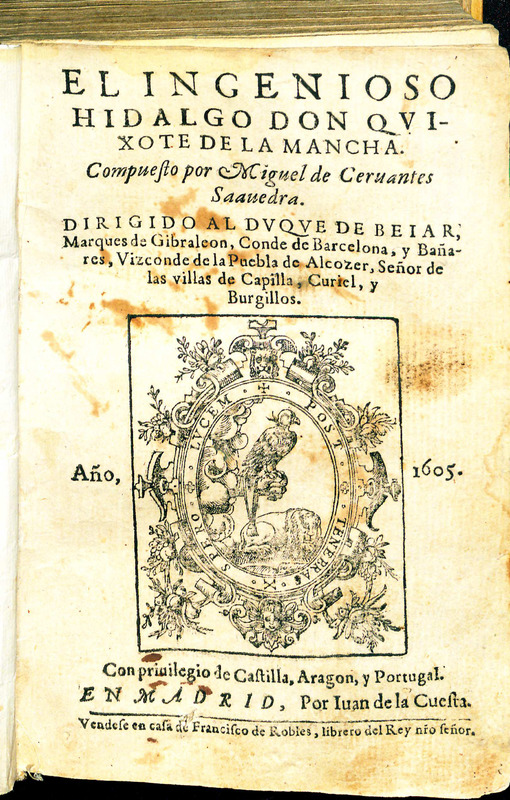

On one hand, Don Quixote held the potential to change early modern Spain’s conception of chivalric tales from tales of honor, heritage, and grandeur, to tales of superficial honor, imagined heritage, and self-aggrandizement. On the other hand, the physical circulation of the novelin comparison to chivalric legends affected its ability to change the “reality” of the knight-errant for many Spaniards. Despite the advent of the printing press, both the ability to purchase books and the ability to read remained limited to the more elite classes in the early seventeenth century. Additionally, in Spain, writers had to send in their manuscripts to the Royal Council of their kingdom and apply for a special permit to publish and print their books. For example, the permit for Don Quixote only allowed it to be printed “por tiempo y espacio de diez años cumplidos” or“for the time and space of ten...consecutive years” and warned that “no otra alguna”, (Luis Andres Murillo) or “no other” printer besides those approved by the censors should print the text (Norton 413). Even though Don Quixote was incredibly popular in early modern Spain, the heavy regulations on selling a book along with the elitist nature of reading limited the number of minds it could reach. Since a vast number of tales that portrayed chivalry in a more heroic and serious light had held a place in Iberian culture from the middle ages, the publication of Don Quixote did not cause a large majority of Spaniards to see chivalric tales as elaborate myths instead of accurate histories overnight.

As Martín De Riquer explains in “Cervantes and the Romances of Chivalry,” the physical circulation of chivalric legends among the lower-classes had created an investment in the grandiose “reality” of the knight-errant that would require work to dislodge. While readers would initially have to purchase Don Quixote at the permitted bookseller, multiple other media existed to transmit traditional chivalric legends to the masses. One of the characters in Don Quixote describes the oral transmission of chivalric legends: “porque cuando es tiempo de la siega, se recogen aqui las fiestas muchos segadores, y siempre hay alguno que sabe leer, el cual coge uno destos libros en las manos, y rodeamonos del mas de treinta, y estamosle escuchando con tanto gusto” (207) “a lot of reapers gather here on holidays, and there are always some who know how to read; and one of them picks up one of these books, and more than thirty of us gather around him” (Ormsby 907). In addition to oral transmission, as De Riquer notes “a good number of books of chivalry…enjoyed exceptionally wide circulation in broadsides and chap books printed on cheap paper,” allowing for distribution to a slightly wealthier but still “uncultivated public” (Ormsby 907). Although it would gain them overtime, in the first few years of its publication, Don Quixote lacked the media of mass circulation that had spread and continued to spread chivalric legends to a larger, less educated audience. As a result, many members of the lower-class public, who constituted the majority of early modern Spain’s population, would continue to think of the knights portrayed in chivalric legends as heroes to aspire to.

Works Cited

Cervantes Saavedra, Miguel de. El Ingenioso Hidalgo: Don Quijote De Al Mancha. Buenos Aires: Espasa-Calpe Argentina, 1940. Print.

———. Don Quixote: The Ormsby Translation, Revised, Backgrounds and Sources, Criticism. Ed. Joseph R. Jones and Kenneth Douglas. Trans. John Ormsby. New York : W.W. Norton, 1981. Print.

Childers, William. Transnational Cervantes. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2006. Print.

Riquer, Martin De. "Cervantes and the Romances of Chivalry." Don Quixote: The Ormsby Translation, Revised, Backgrounds and Sources, Criticism. Ed. Joseph R. Jones and Kenneth Douglas. Trans. John Ormsby. New York : W.W. Norton, 1981. Print.