Japanese Modernism Across Media

The Nude

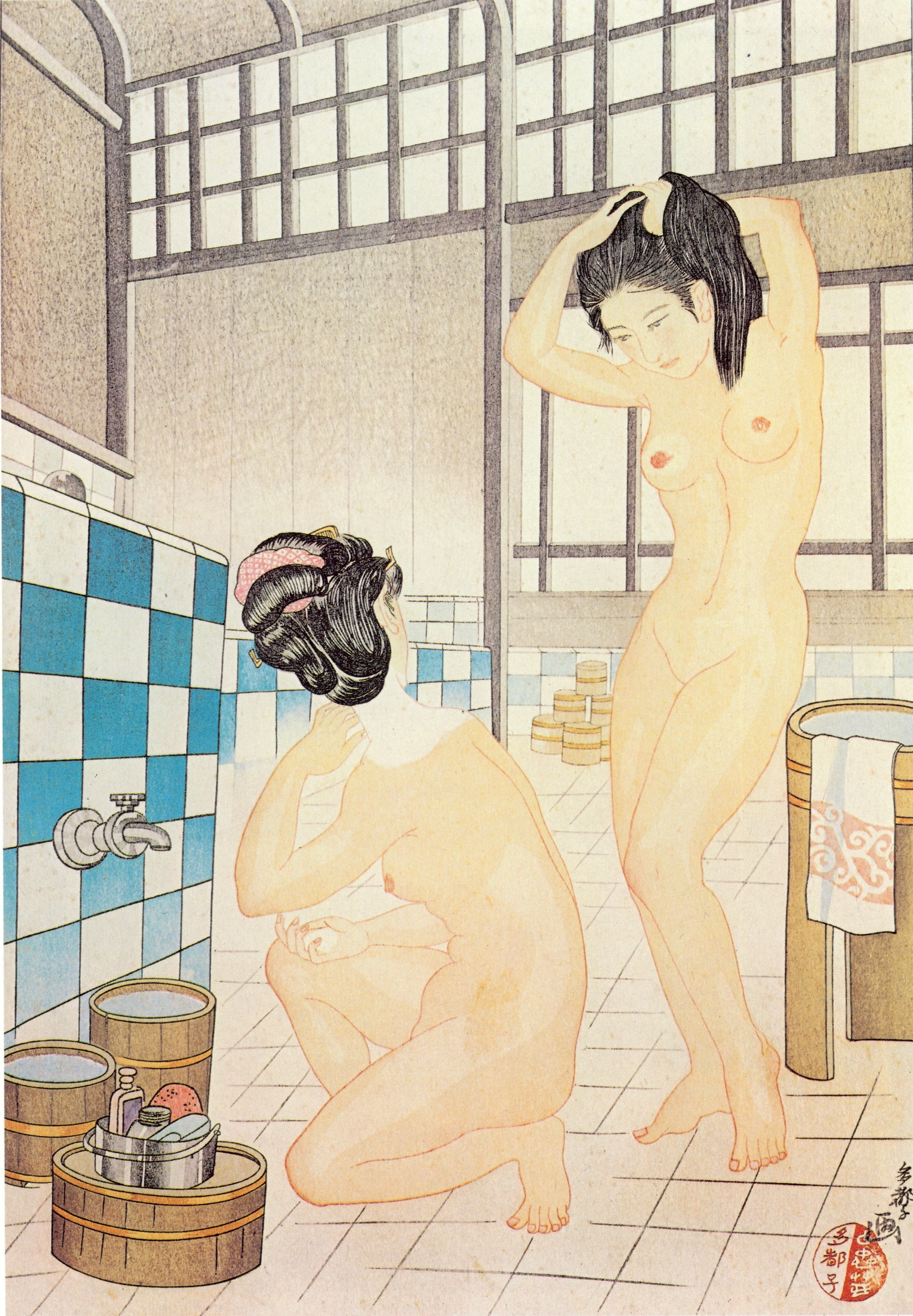

The culture of Japanese printmaking did not fully blossom until the Edo-period (1603-1868) with ukiyo-e or the prints of ‘floating world’. However, the nude was never its own genre within ukiyo-e prints, but instead only appeared in the shunga (the term used for erotica in printmaking, painting, and book illustrations). More specifically full nudity was an exception and when any form of nudity did appear in prints or paintings, it was nearly always within an erotic context. Nudity also appeared in a few other subjects such as female abalone divers, the mountain woman of Japanese folklore (Yamauba), and scenes relating to the bath. Although these images did not portray the same overt sexuality as the shunga, their sexual underpinnings were clearly present. However, along with the government’s endorsement of Western-style painting came the larger role of the nude in art.[1]

The nude as a subject in high art had a long tradition in Europe, but had never been a part of Japan’s historical artistic traditions. The turning point occurred when the Western artists who favored nude models were brought to Japan by the Japanese government to teach Western painting techniques. The government hoped an acceptance of the nude image as a legitimate art subject was a sign of not only Japan’s modernity, but also in the eyes of the Western powers, its civility. Nevertheless, although the government and much of the artistic community had accepted the nude as legitimate subject matter, the public did not as easily accept it. For example in 1895 at the Fourth National Exhibition for the Promotion of Industry in Kyoto, Kuroda Seiki’s nude entitled morning toilette, prompted public outrage. As Nihon No Hanga writes, “The incident shows that despite a long, but officially illegal, tradition of erotic art, the general audience in Japan had not yet embraced the nude as a legitimate genre.”[2] With this public opinion in mind, it is somewhat surprising that any nudes were created. However, capitalism began its reign, and shin hanga prints were driven by the publishers who were driven by profit. Wantanabe Shōzaburō, one of the publishers at the heart of the shin hanga movement, discovered that by embedding his nudes and semi-nudes within the context of bathing or applying make-up, he could avoid controversy, still manage to appear modern, and most importantly, cultivate the lucrative Western market. His work and the works of other shin hanga artists/publishers caught the eye of foreigners, mainly Americans, who became seriously interested in these prints and were willing to pay higher prices for them than for traditional/classical works from the ukiyo-e tradition. With this lucrative confluence of modernity and simultaneous avoidance of censorship, it is no surprise that, with the exception of Ishikawa Toraji’s work, most of the resulting images of nudes and semi-nudes made and displayed in this exhibit are set within the acceptable contexts of bathing or applying make-up.[3]

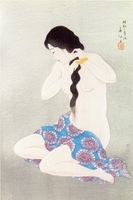

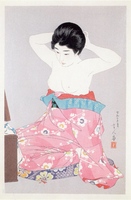

Itō Shinsui (1898-1972)

from 'New Twelve Images of Beauties' 1922-23

The remaining images in this series can be found in The Female Image in Shin Hanga Prints: Modern Beauties

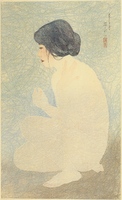

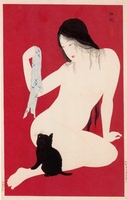

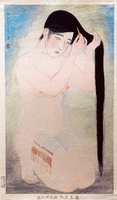

Takahashi Hiroaki (Kōmei)

1871-1945

Hiroaki, whose real name was Katsutarō, was born in Tokyo in 1871. Although having an artist's name was a common practice, Hiroaki had two additional artist's names, Shōtei and Kōmei. Hiroaki also studied nihonga painting. His teacher was Matsumoto Fūko. Many of his prints were intended for export, but he also worked with Watanabe during the 1910-20s. In addition to designing prints he also illustrated textbooks and novels.[4]

[4] Hamanaka Shinji and Amy Reigle Newland, The Female Image: 20th Century Prints of Japanese Beauties (Leiden: Hotei, 2003), 212.

Natori Shunsen (1886-1960)

Three beauties by Shunsen: the third image can be found in The Female Image in Shin Hanga Prints: Modern Beauties

From Itō Shinsui's 'The First Series of Modern Beauties' 1929-31

The other images are displayed in The Female Image in Shin Hanga Prints: Modern Beauties

Torii Kotondo (1900-1976)

Tipsy, no.1 and Rouge, no.6 are displayed in, The Female Image in Shin Hanga Prints: Moga

Make-up, no.2, Nails, no.3, and Pupils of the eyes, no.4 are displayed in The Female Image in Shin Hanga Prints: Modern Beauties

Narita Morikane ?-?

Only six of the twenty images in the series could be located. The remaining three are displayed in The Female Image in Shin Hanga Prints: Modern Beauties

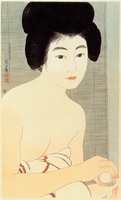

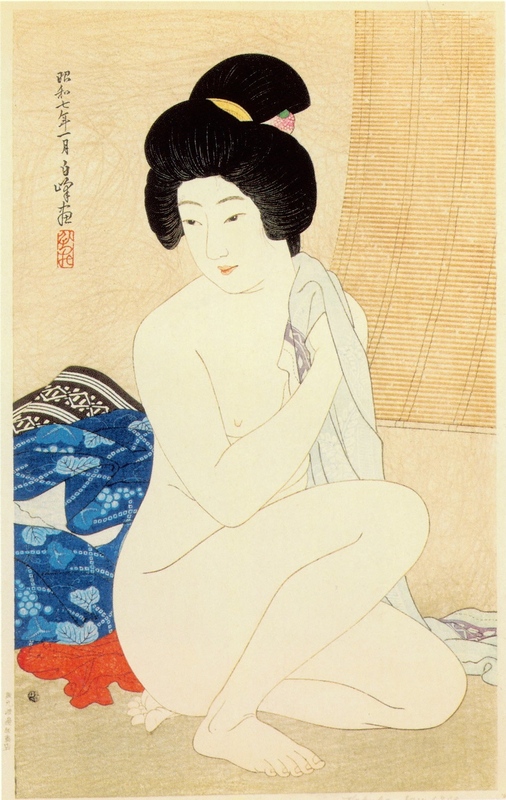

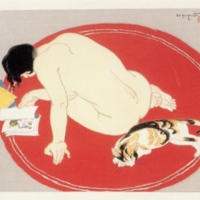

Hirano Hakuhō (1879-1957)

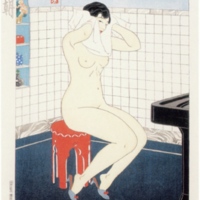

Hakuhō was born in Kyoto and studied many different styles of painting such as nihonga and ukiyo-e, as well as other classical and modern styles. Watanabe Shōzaburō published many of Hakuhō’s prints such as After a Bath and Before the Mirror in 1932. After a Bath was particularily well-received abroad, where it sold out at the Toledo Museum Print Show of 1936.[5]

[5] Shinji and Newland, The Female Image, 208.

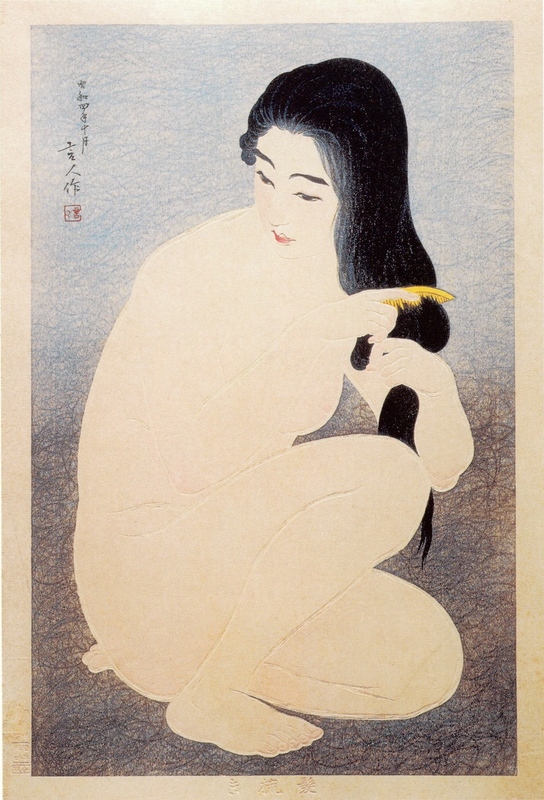

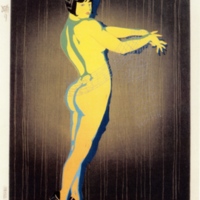

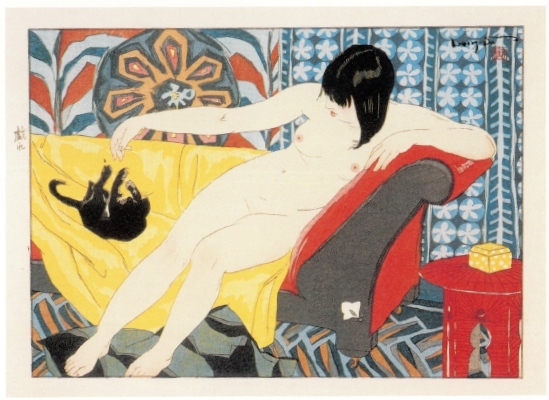

Ishikawa Toraji (1975-1964)

'Ten Types of Female Nudes' 1935

For further information about this series as well as Ishikawa Toraji, please visit The Female Image in Shin Hanga Prints: Visual Essay

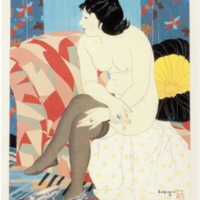

Itō Shinsui's 'The Second Series of Modern Beauties' 1931-36

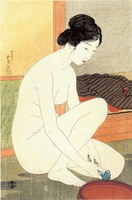

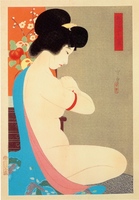

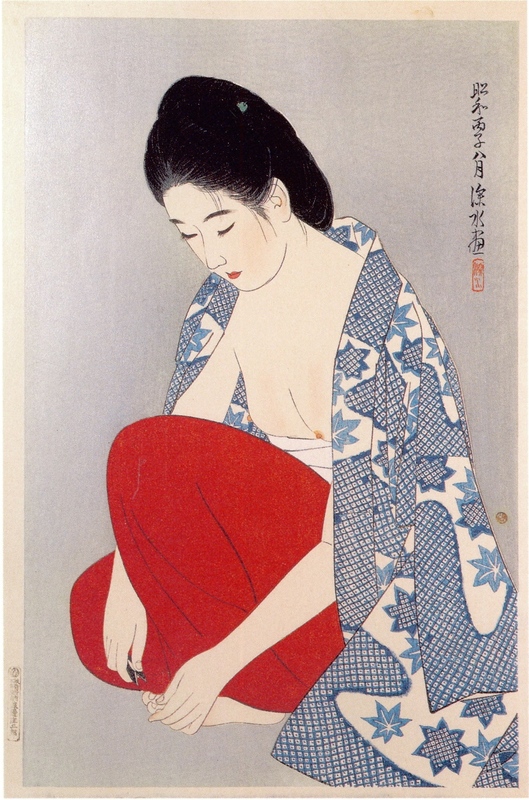

Nails

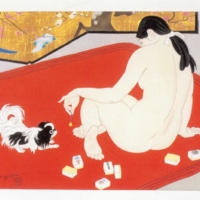

As with many other Shinsui prints, Nails is a triangular composition, lending stability to his design. This print captures a young woman kneeling to trim her toenails, an intimate moment accentuated by her state of undress. Her face is relaxed and composed, lending a peacefulness or gracefulness to the scene that becomes almost elegant as a result.[6]

[6] Kendall H. Brown, Nozomi Naoi, and Allen Hockley, The Women of Shin Hanga: The Judith and Joseph Barker Collection of Japanese Prints, ed. Allen Hockley (Hanover, NH: Hood Museum of Art, 2013), 188.

The other images in the series can be found in The Female Image in Shin Hanga Prints: Modern Beauties.

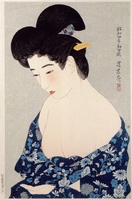

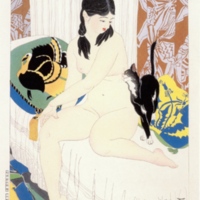

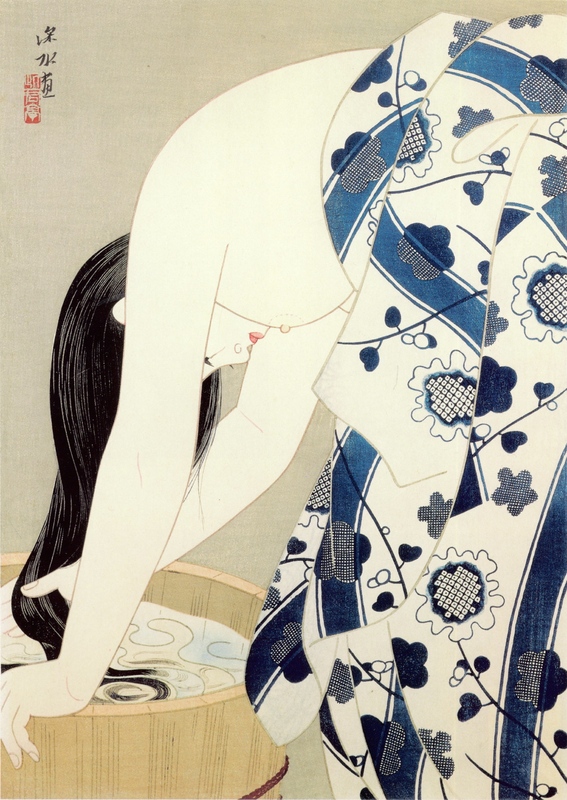

Itō Shinsui (1898-1972)

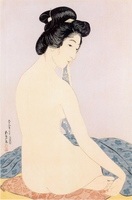

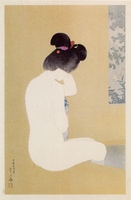

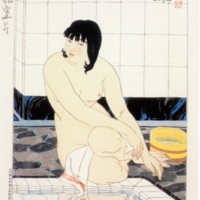

Hair

Shinsui designed Hair to commemorate his designation as Preserver of Intangible Cultural Properties (Jūyō Mukei Bunkazai Hojisha) in 1952. Artists awarded this distinction became referred to as “living national treasures” (nigen kokuhō). With the subject of this print (a woman washing her hair over a large wooden tub) being common to both Tokugawa and Meiji-period art, it was an appropriate choice of topic by Shinsui. While the subject may be traditional, however, Shinsui’s design is modern in the sense that the fabric patterns are quite abstract and geometrical, flattening out the right half of the image.[7]

[7] Brown et al, The Women of Shin Hanga, 240.