Japanese Modernism Across Media

Moga

It was not until the Great Kantō earthquake in 1923, that the Modern Girl, or modan gaaru, abbreviated to moga, emerged. As Nihon No Hanga writes, “There was a sense that with the reconstruction of Tokyo, the traditional restrictive values would remain buried under the rubble.”[1] The term moga first appeared in 1924 by author Kitazawa Shuichi in the women’s magazine Josei.[2] Like many concepts, the moga was multifaceted and for many very difficult to digest. The focus of Nihon No Hanga’s fifth exhibition in the spring of 2011 entitled “Feminine and Independent,” was the moga. The catalogue included an incredibly comprehensive definition and description of the moga and I believe it does far greater justice to defining the Modern Girl than I ever could:

In reading these constructions of the new ‘sociological type’ one sees the stacking of character traits: apolitical, autonomous, liberated from age-old conventions, animated, fond of double entendre, erotically aggressive, flirtatious, promiscuous, anarchistic, militant and Westernized. Then her outer appearance: cropped hair, short shirts, bare legs, wearing make-up and jewelry. Her behavior included ginbura or ‘Ginza cruising’ referring to going out in Ginza and moving from bar to bar, going to the movies, dancing in the dance halls and actively pursuing men. She would be seen smoking and drinking cocktails. And perhaps above all, she was an active consumer, demonstrating her financial independence.[3]

As Nihon No Hanga makes a point of stating, “No woman fitted all these traits.”[4]

It is important to note that the moga was part of the larger phenomenon of the Modern Women. The other two types of women were the self-motivated housewife (shufu) and the rational, extroverted professional working woman (shokugyo fujin).[5] All three types of women, oftentimes in widely different ways, played a significant role in challenging the existing gender norms and in general repositioning women in Japanese society. As the following collection will demonstrate, due to the fact that the Modern Girl/moga strongly stood out and caused the most controversy, she was more frequently the focus and subject for printmakers, rather than the other two types of women.[6] However, as no Modern Girl fit the long list of traits listed earlier, the prints of these moga are quite diverse, ranging from those in which the hairstyle is the sole marker of modernity to ones in which the female’s full attire from head to toe denotes her modernness.

[1] Chris Uhlenbeck, Maureen De Vries, and Elise Wessels, Feminine and Independent: The Modern Women of Pre-war Japan (Amsterdam: Nihon No Hanga, 2011), 9.

Yamamura Kōka (Toyonari) 1886-1942

Kōka, whose real name is Toyonari, was born in Tokyo. Kōka studied nihonga at the Tokyo Art School. As his interest in theater grew, he designed numerous prints of actors and the theatrical world in the series ‘Rien no hana’ (‘Flowers and the theatrical world’), published by Watanabe between 1920-1922. Kōka self-published Dancing at the New Carlton Hotel in Shanghai in 1924.[7]

[7] Hamanaka Shinji and Amy Reigle Newland, The Female Image: 20th Century Prints of Japanese Beauties (Leiden: Hotei, 2003), 212.

Dancing at the

New Carlton Hotel in Shanghai

1924

This print is significant as it is the first shin hanga print to depict modern girls (moga), albeit in China as opposed to Japan. Interestingly, the woman on the left side of the image has distinctly Western facial features. One possible interpretation of this is that Koka’s motivations were to present an accurate depiction of the very diverse and heavy Western foreign presence in Shanghai.[8] Regardless of his motivation, however, this image is full of markers of modernity associated with the modern girl or moga. Brown et al list the features of the modern girls in this print to include: “bobbed hair, lipstick and mascara, peacock fans, floppy hats, cocktails, and taxi dancing in gaily patterned dresses that reveal bare arms, backs and necks.”[9]

[8] Kendall H. Brown, Nozomi Naoi, and Allen Hockley, The Women of Shin Hanga: The Judith and Joseph Barker Collection of Japanese Prints, ed. Allen Hockley (Hanover, NH: Hood Museum of Art, 2013), 190.

Ishii Hakutei (1882-1958)

Visit

from 'Twelve Images of Modern Women' 1932

I was personally suprised by the range of styles of Hakutei's prints in this exhibit. Hakutei and his series ‘Twelve Views of Tokyo’ was discussed in the previous section, “Modern Beauties.” In my opinion, Visit from 'Twelve images of Modern Women' contrasts sharply with the prints in ‘Twelve Views of Tokyo.’ The woman in Visit is quite modern with short hair, a stylish hat and Western-style dress. Her hand-held purse is another sign of her modernity. To emphasize her contemporaneousness, she is sitting in a Western-style chair. Unfortunately the rest of the images in this series could not be located.

Yamakawa Shūhō (1898-1944)

Autumn

In general most of a series of shin hanga prints has a sense of cohesion, but occasionally in a series containing a larger number of prints, one or two of the prints does not quite blend in as well. I find it interesting that this occurs in Shūhō’s very short series titled, ‘Four Images of Women.’ In my opinion, the fourth image in this series, Autumn, is quite unique. Shūhō has clearly depicted a modern girl with her modern hairstyle and card-patterned kimono, while the other three images depict the modern beauty with her more classic hairstyle.

from the series 'Four Images of Women' 1927-28 see The Female Image in Shin Hanga Prints: Modern Beauties for other images in the series

Watanabe Ikuharu's 'Competing Beauties During the Showa Era'

The remaining images are displayed The Female Image in Shin Hanga Prints: Modern Beauties

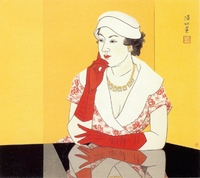

Kobayakawa Kiyoshi (1889-1948)

Kiyoshi’s first image in his series ‘Women’s Manners of Today’ is bold and striking as he has depicted a young woman who seems to embody every aspect of the quintessential modern girl. She has the daring bob haircut and is also wearing lipstick as well as nail polish. Another aspect of the modern girl was her status as a consumer. In this case, the woman’s ring, string of pearls and wristwatch are evidence of her consumer status. Lastly, the cigarette in her hand as well as the cocktail glass on the table in front of her, suggest the promiscuous aura that often plagued the modern girl.[10]

[10] Brown et al, The Women of Shin Hanga, 216.

Make-up, no.2, Nails, no.3, and Pupils of the eyes, no.4 are displayed in The Female Image in Shin Hanga Prints: Modern Beauties

Glossy dark hair, no.5 is displayed in The Female Image in Shin Hanga Prints: The Nude

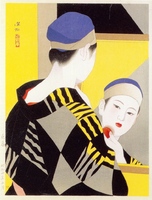

Kobayakawa Kiyoshi (1889-1948) - Dancers

Kiyoshi continued to design stunning and striking prints with the following three prints of women dancing. All of these women seem to be depictions of the moga. The first image is of a graceful woman wearing a long-sleeved kimono and obi. Although her attire would not suggest such, her wavy hair is a clear indicator that she is a moga. The second image is stunning for its composition. There is no doubt that this woman is a moga. She wearing a Western-style dress which exposes her arms and legs as well as bright red high-heels and a cloche hat. Lastly we come to the modern barefoot dancer who also is wearing a dress that exposes her arms and legs. Although her hair is pushed back due to the headband she is wearing, it is clearly quite short, indicating her moga status.[11]

An interesting note about modern dance in Japan: dance halls were something that sprouted up at the turn of the 20th century. Women could be employed as taxi dancers or as stage performers. There was a wide range of dance styles that drew from both Japanese and Western influences as well as just plain improvisation. Many of these dances were not intended solely for their artistic quality, but were sexualized to please the mostly all-male audiences.[12]

[11] Brown et al, The Women of Shin Hanga, 228.

Itō Shinsui (1898-1972)

Clock and Beauty (IV)

see The Female Image in Shin Hanga Prints: Modern Beauties for 'Clock and beauty I, II, & III''

![February [lunar calendar] – Early spring February [lunar calendar] – Early spring](https://ds-omeka.haverford.edu/japanesemodernism/files/thumbnails/cc57e1d33f25ad756d9a6a3c22959323.jpg)

![April [lunar calendar] – Shadows of cherry blossoms April [lunar calendar] – Shadows of cherry blossoms](https://ds-omeka.haverford.edu/japanesemodernism/files/thumbnails/45ff11105b32efd9048da7e8bd26a40d.jpg)

![July [lunar calendar] – Chorus of Cicadas July [lunar calendar] – Chorus of Cicadas](https://ds-omeka.haverford.edu/japanesemodernism/files/thumbnails/ec24df944dadc182c7bb8abaaced0eb6.jpg)

![September [lunar calendar] – Rouge September [lunar calendar] – Rouge](https://ds-omeka.haverford.edu/japanesemodernism/files/thumbnails/b9182dcf2916b17aaaa3c9af6088b622.jpg)

![November [lunar calendar] – Drizzling rain November [lunar calendar] – Drizzling rain](https://ds-omeka.haverford.edu/japanesemodernism/files/thumbnails/1e17da3f8739d7b04948919b5993429b.jpg)

![December [lunar calendar] – Snow sky December [lunar calendar] – Snow sky](https://ds-omeka.haverford.edu/japanesemodernism/files/thumbnails/028a306678ebf11099f233191282045f.jpg)