Japanese Modernism Across Media

Modern Beauties

Moga

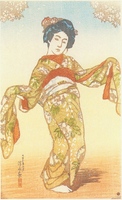

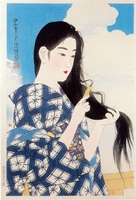

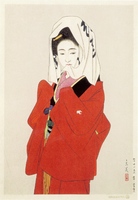

Prints of beauties (bijinga) have a long tradition in Japanese printmaking, dating back to the beautiful women of ukiyo-e prints. With regards to bijinga in shin hanga, they are the most prolific iteration of the female image. For example, prominent shin hanga artists such as Itō Shinsui (1898-1972), Hashiguchi Goyō (1880-1921), Kobayakaw Kiyoshi (1889-1948) and Torii Kotondo (1900-1976) and their shin hanga colleagues produced over 200 prints of women. [1] In Nihon No Hanga, Chris Uhlenbeck et al write, “these shin hanga artists generally chose to portray their beauties in a traditional style, emphasizing a tranquil beauty and showing the subjects involved in activities traditionally associated with women, such as applying make-up, stepping out of the bath, or adjusting their hair in the mirror.”[2] As they seem heavily steeped in more traditional displays of the female image, it may be difficult to understand how these prints are considered modern. That is in part due to the fact that the modernity of these prints is much more nuanced than the obvious visual display of modernity seen in the latter sections of “the moga”and “the nude”. Nevertheless, these prints of beauties are also modern as they are new forms and presentations of the female image and quite a departure from ukiyo-e prints. As a comparison is essential to understanding the modernity in the shin hanga prints of female beauty, the first few images are some rather famous ukiyo-e prints of ‘beautiful women.’ If desired, please go to any of the following sites for further information and/or images of ukiyo-e prints.

- http://archive.artsmia.org/art-of-asia/explore/explore-collection-ukiyo-e.cfm

- http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/ukiy/hd_ukiy.htm

- http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/ukiyo-e/intro.html

- http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/articles/u/ukiyo-e_paintings_and_prints-1.aspx

- http://ukiyo-e.org/

[1] Chris Uhlenbeck, Maureen De Vries, and Elise Wessels, Feminine and Independent: The Modern Women of Pre-war Japan (Amsterdam: Nihon No Hanga, 2011), 3. [2]Uhlenbeck, Feminine and Independent, 3.

Ishii Hakutei (1882-1958)

Although his shin hanga prints are presented here, Ishii Hakutei is more highly regarded as a leading artist in the sosaku hanga (creative print) movement. Hakutei was born in Tokyo and received training early on in his life in nihonga (Japanese-style painting) from his father who was a nihonga artist. After studying Western-style painting at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts and two later trips to Europe, Ishii Hakutei became a life-long proponent of Western-style art. In addition to being an artist, he was also a noted poet and essayist and served as the editor of two early-twentieth-century art journals, Myojo and Hosun.[3]

[3] Kendall H. Brown, Nozomi Naoi, and Allen Hockley, The Women of Shin Hanga: The Judith and Joseph Barker Collection of Japanese Prints, ed. Allen Hockley (Hanover, NH: Hood Museum of Art, 2013), 117.

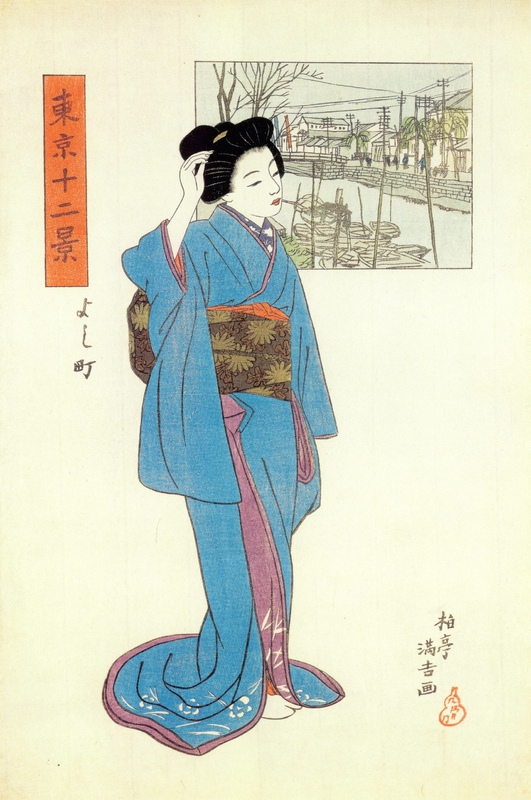

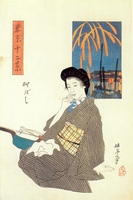

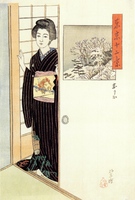

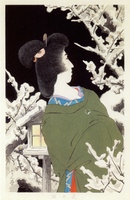

'Twelve Views of Tokyo' 1910/1914-17

As Brown et al write, "This series was an important transitional work between ukiyo-e and what would eventually become the shin hanga movement."[4]

The women of these prints are geisha, who by 1918 numbered approximately seven thousand. Although the composition of this series (figure, landscape inset, title, subtitle signature, and seal) is steeped within the ukiyo-e tradition, Hakutei’s individualized portraits of highly stylized and distinctive faces were a vast departure from the ukiyo-e tradition of generic facial characteristics. For unknown reasons, the three remaining images of the series were never created/completed.[5]

[4] Brown et al, The Women of Shin Hanga, 126.

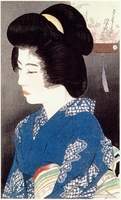

Hashiguchi Goyō (1880-1921)

Due to his premature death from meningitis in 1921, Goyō’s career as a shin hanga artist was brief. Goyō’s choice of subject and format was as eclectic as his formal art training. He started off studying nihonga, but then transitioned into yoga painting. Goyō painted screens (sliding screens and folding screens) which had nihonga landscapes and flower-and-bird paintings. He painted in both oil and watercolor. Although Goyō exhibited interest in depicting the female image throughout his career, the theme came to play a prominent role in his prints beginning in the early 1910s. Due to his training in Western techniques, he paid great attention to accurately depicting realistic garments and fabrics and his figures tended to be anatomically accurate.[6]

[6] Brown et al, The Women of Shin Hanga, 114-116.

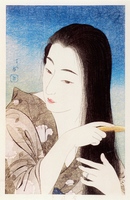

Itō Shinsui (1898-1972)

Itō Shinsui had a long and illustrious career for which he was publically recognized and rewarded. For example, in 1952 he was recognized for his contributions by the Commission for the Protection of Cultural Properties; in 1958 he was appointed to the Japan Art Academy; in 1970 he received the prestigious civic award, the Order of the Rising Sun; and two of his works were posthumously honored with commemorative postage stamps in 1974 and 1983. According to Allen Hockley, “Shinsui is now regarded by scholars as one [of] the great bijinga artists of the twentieth century. No other shin hanga artist came close to matching his output of bijinga.”[7]

Shinsui’s earliest forays into the world of print began at the age of eleven when he worked as an assistant typographer and lithographer for Tokyo Printing Company. Shortly thereafter he began exhibiting his paintings and supporting himself by illustrating newspapers, magazines, and popular novels in many different media. By the age of twenty, he was exhibiting his works in the Bunten, a national art show. He established a painting academy in 1927, and only four years later had more than one hundred students enrolled. In 1916 Shinsui began his collaboration with Watanabe. This would be the beginning of a twenty-five year relationship. During this period, Shinsui designed several hundred prints of the female image for Watanabe and other publishers. Unlike many artists, Shinsui was able to continue to paint and design prints after World War II.[8]

[7] Brown et al, The Women of Shin Hanga, 118.

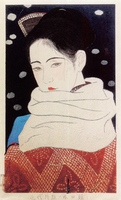

‘New Twelve Images of Beauties’ is one example of Shinsui’s collaboration with Watanabe. This series was actually Shinsui’s first bijinga series. It seems that the prints sold well since Watanabe published these designs in editions of two hundred each, where one design was sold each month. On each design is an inscribed date indicating the season or month in which it was made.[9]

[9] Brown et al, The Women of Shin Hanga, 118.

The remaining three images in this series are displayed in The Female Image in Shin Hanga Prints: The Nude

Miki Suizan (1887-1957)

Miki Suizan was born in Hyogo in 1887. Like many of the artists for shin hanga prints, he was trained in nihonga (Japanese-style) painting. His paintings were also regarded highly enough to be shown in the Bunten. Although he was heavily influenced by ukiyo-e and kept close to that tradition, his ‘The First Series Selected views of Kyoto’ demonstrates that he also developed his own unique style.[10]

[10] Hamanaka Shinji and Amy Reigle Newland, The Female Image: 20th Century Prints of Japanese Beauties (Leiden: Hotei, 2003), 210.

'The First Series Selected Views of Kyoto' 1925

'Four Images of Women' 1927-28

Shūhō, whose real name was Yoshio, was born in Kyoto in 1898 and and moved to Tokyo at a young age. Shūhō received his education with regard to bird and flower paintings from Ikegami Shūhō, and regarding bijinga paintings from Kaburaki. His works received awards in the ninth and eleventh Teitens (National Exhibits). Shūhō’s prints of bijinga were published by Watanabe as well as Bijutsu-sha.[11]

The first image in this series is displayed in The Female Image in Shin Hanga Prints: Moga.

Natori Shunsen (1886-1960)

'Three Beauties by Shunsen' 1928

Unlike Shinsui, Shunsen is much better known and highly regarded for his actor prints than for his bijinga. After relocating his family to Tokyo, he began studying nihonga and oil painting. Before turning to prints, Shunsen supported himself by illustrating serialized novels.[12]

The two remaining images in this series are nudes and are displayed in 'The Female Image in Shin Hanga Prints: The Nude'

Itō Shinsui - Continued

'The First Series of Modern Beauties' 1929-31

The remaining two images in this series are displayed in The Female Image in Shin Hanga Prints: The Nude

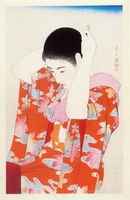

Torii Kotondo (1900-1976)

[13] Brown et al, The Women of Shin Hanga, 124.

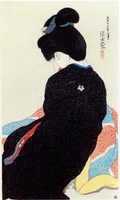

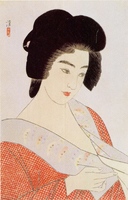

Kobayakawa Kiyoshi (1889-1948)

Kiyoshi’s output of bijinga prints was also quite limited. He only designed thirteen prints, all in the early 1930s, six of which compose the self-published series entitled, ‘Modern Fashions’. Like a number of shin hanga artists, Kiyoshi studied nihonga with Kaburagi Kiyokata. His paintings were well received in the art world, and in 1934 the Matsukanaya department store honored him with a solo exhibit.[14]

[14] Brown et al, The Women of Shin Hanga, 120.

This series consists of six of Kyoshi’s self-published prints. The series was published between February 1930 and March 1931. [15] Although Tipsy (see Moga section) gets the most notice, the series as a whole is quite interesting. The eclectic aspect of all six prints seems to represent the diverse depiction of the modern women in shin hanga.

[15] Brown et al, The Women of Shin Hanga, 216.

Tipsy, no.1 and Rouge, no.6 are displayed in, The Female Image in Shin Hanga Prints: Moga

Glossy dark hair, no.5 is displayed in The Female Image in Shin Hanga Prints: The Nude

Kobayakawa Kiyoshi - Continued

Narita Morikane ?-?

According to Shini and Newland, “No biographical details are known. In 1931 Shinbi-sha published the series ‘Twenty-four Figures of Charming Women’ which Morikane designed together with Kasen.”[16]

[16] Shinji and Newland, The Female Image, 211.

'Twenty-four Figures of Charming Women" 1931

Only six of the twenty-four could be found. The remaining three are displayed in The Female Image in Shin Hanga Prints: The Nude

Itō Shinsui - Continued

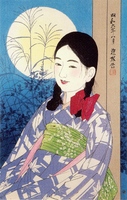

'The Second Series of Modern Beauties' 1931-36

Although there is quite a bit of overlap in subject matter between the first and second ‘Series of Modern Beauties’, Shinsui has managed to present the women very differently while also including some new images. Unlike the first series, Shinsui took an extended amount of time (over five years) to complete this second series of prints. During this time, it appears he was working on several projects, including another series that comprised one hundred prints.[17]

[17] Brown et al, The Women of Shin Hanga, 188.

The last image is displayed in The Female Image in Shin Hanga Prints: The Nude

Watanabe Ikuharu (1895-1975)

Not much is known about Ikuharu regarding his prints. However we do know a little about his activities as a painter. Ikuharu was born in Nagoya. He attended the Kyoto Municipal School of Painting between 1922-25 and was taught by Yamamoto Shunkyo.[18]

[18] Shinji and Newland, The Female Image, 212.

'Competing Beauties During the Showa Era'

The remaining images are displayed in The Female Image in Shin Hanga Prints: Moga

Shimura Tatsumi (1907-1980)

Tasumi, whose real name is Sentarō, was born in Takasaki, Gunma. His designs of bijinga have the signature characteristics of long eyelashes and blurred pupils. In addition to designing prints, Tatsumi did quite a bit of illustrating in magazines, newspapers, novels and on covers of books.[19]

[19] Shinji and Newland, The Female Image, 211.

'Five Figures of Modern Beauties' 1953

Itō Shinsui - Continued

'Clock and Beauty I- IV' 1964

The fouth images in this series is displayed in The Female Image in Shin Hanga Prints: Moga

![Maiko [apprentice geisha in Kyoto] Maiko [apprentice geisha in Kyoto]](https://ds-omeka.haverford.edu/japanesemodernism/files/thumbnails/18eb8a11df69605a84364cbe0c53c1dd.jpg)

![January [lunar calendar] – The New Year’s Week January [lunar calendar] – The New Year’s Week](https://ds-omeka.haverford.edu/japanesemodernism/files/thumbnails/134c3e76933f661f2a3f0c50cffa05f2.jpg)

![March [lunar calendar] – The Girl’s Festival March [lunar calendar] – The Girl’s Festival](https://ds-omeka.haverford.edu/japanesemodernism/files/thumbnails/bfb4f99192b54bb0c2de4ceb5a3ff36f.jpg)

![May [lunar calendar] – Season of young leaves May [lunar calendar] – Season of young leaves](https://ds-omeka.haverford.edu/japanesemodernism/files/thumbnails/deccf11c900c79310d8c68b8c19d0285.jpg)

![June [lunar calendar] – After a Bath June [lunar calendar] – After a Bath](https://ds-omeka.haverford.edu/japanesemodernism/files/thumbnails/fa61522047001402ad6b5e399d3df053.jpg)

![August [lunar calendar] – Indian summer August [lunar calendar] – Indian summer](https://ds-omeka.haverford.edu/japanesemodernism/files/thumbnails/d7979483cd8baa8a501f3cbd416c1cd8.jpg)

![October [lunar calendar] – Pensive (suggested title) October [lunar calendar] – Pensive (suggested title)](https://ds-omeka.haverford.edu/japanesemodernism/files/thumbnails/e5359aca7033ebddb65cef7e2714f059.jpg)

![Marumage [hair style of married woman] Marumage [hair style of married woman]](https://ds-omeka.haverford.edu/japanesemodernism/files/thumbnails/e92fe75fe2fde5f810413c04197c2c21.jpg)