Japanese Modernism Across Media

The Female Image in Shin Hanga Prints

Introduction

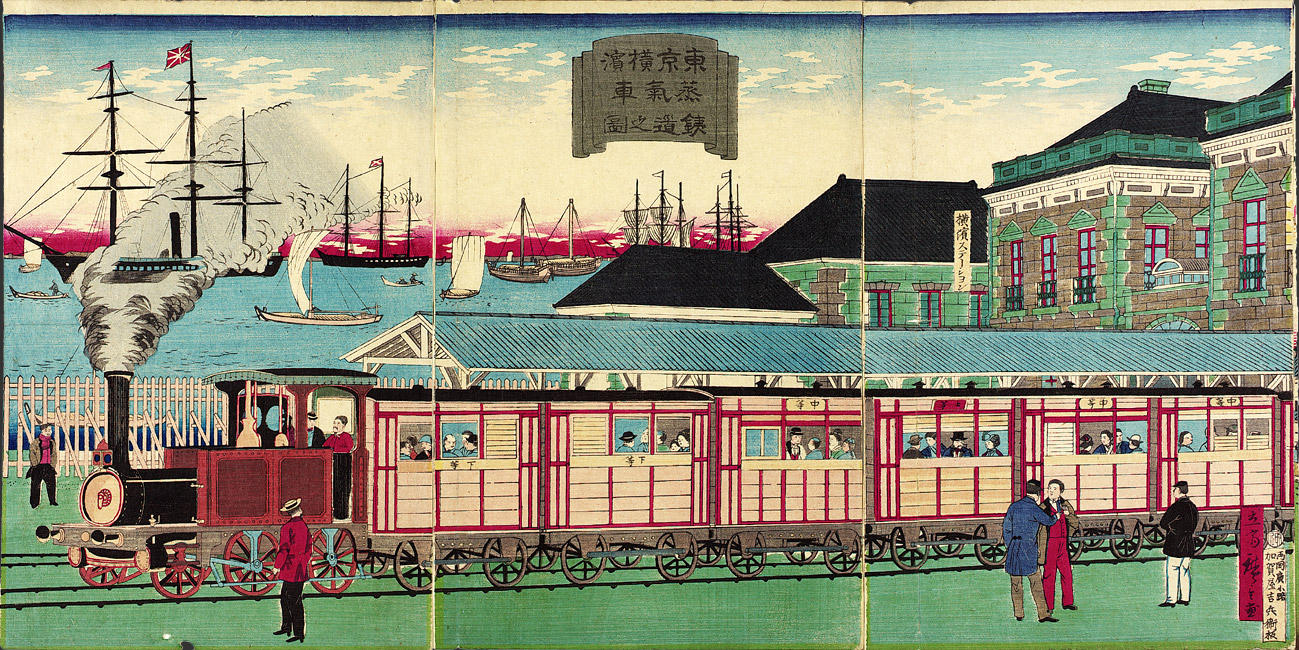

Steam Train between Tokyo and Yokohama

The period from 1868-1945 was one of rapid transformation for Japan. When this era of Japanese history is discussed, it is frequently with respect to the modernization and Westernization that occurred during this period, which, in the eyes of the Western imperial powers, allowed it to change from a “backwards” and “feudal” nation, to a threat to the Western imperial hegemony. However, the transformation that occurred in Japan was not solely political; instead it was all encompassing. More specifically, during this seventy-five year period, as Christine M.E. Guth writes, “Japanese culture underwent far-reaching changes, many of which had profound implications for the formation of modern Japanese national identity.”[1] Because these changes were all encompassing, they eventually entered into the realm of art, and as a result we can examine the art of this period to help gain an understanding of the complex transformations occurring at this time in Japanese history. This exhibit will focus on the period of 1900-1945, as it took these four and a half decades for changes to be fully realized and implemented.

In an effort to protect their country from being divided and distributed among the Western imperial nations, as had many of its closest neighbors such as China and Korea, Japan decided to try to outplay the West at its own game. More specifically this meant transforming the country into an imperialist power that would garner the respect of the other dominant world powers. Japan therefore took the route of absorbing, learning and then mastering anything Western, be it political theory to clothing and fashion to artistic techniques. We see evidence of this modernization and Westernization in the depiction of the female image in the medium of shin hanga prints. However, before we can delve into the female image itself, we must establish a background understanding on the artistic genre of shin hanga prints.

Shin Hanga Prints

Shin hanga, translated to be “new print movement,” was closely tied to the traditional woodblock printing form of ukiyo-e prints. Ukiyo-e, which means “pictures of the floating world,” was a form of escapism for the Edo period (1603-1868) middle/merchant class. The subjects of these prints were limited to beautiful women, beautiful places and the Kabuki Theater. The publisher worked with artists to obtain a design, and then supervised what could commonly be referred to as the craftsmen, who were responsible for different aspects of the print such as carving the woodblocks, prepping the paper and inking the print. These prints found a niche in the Western art market which raised their reputation from low to high art.[2]

However, shin hanga prints (a term coined by the movement’s central advocate, publisher Watanabe Shōzaburō), was not strictly speaking a derivative of the ukiyo-e print. As Hollis Goodall-Cristante writes,

The central advocate of the shin-hanga movement, Watanabe Shōzaburō (1885-1962, sought to publish works that represented each artist’s creative vision while utilizing traditionally trained carvers and printers as the artists’ “arms and legs” to produce the highest-quality artistic prints. These new prints were distinguished from illustrations, reproductions, and other derivative works by their unique designs and the direct involvement of artists in their production. While subject matter was generally limited by print publishers to actors, birds and flowers, beauties, landscapes, and townscapes, paralleling the main themes of formularized ukiyo-e prints, the shin-hanga artists’ naturalistic treatment of these themes reflected changes in their artistic environment and society generally. Moreover, their designs reveal an exposure to Western art, which had been imported and whose methods were advocated by the government during the early Meiji era.[3]

As Goodall-Cristante, states, the shin hanga movement was greatly shaped by Western artistic influences and therefore is a subject of focus for learning about and gaining an understanding of the complicated and fascinating experiences during the period of modernization in Japan.

In addition, beginning at the tail end of the Meiji period (1868-1912), the audience for shin hanga prints moved from being solely domestic to also having an international scope. Although it is incredibly important to keep in mind the intended audience for a piece of artwork, there is little information about which prints were created for a domestic versus an international audience, making it difficult to interpret the prints through this lens.

The Female Image

The female image is an important subject to study in Japanese art as it has had a long and prevalent role. Many paintings of women have survived from different periods with the earliest being the 8th century, continuing up through the Edo period with ukiyo-e prints and further up to the modern day.[4] As it played a prominent role in Japanese art, the study the female image is another excellent avenue to follow in studying modernization in Japan. Looking at the female image in conjunction with shin hang prints is particularly useful as it narrows the view down to a more manageable size. By studying the female image through shin hanga, it is possible to see the way in which the female image changed over time and in what ways it reflected new fashions or new artistic techniques. Lastly by studying the female image in shin hanga prints, we can start to gain an understanding of how women were viewed by society and whether or not that view was modernizing in the same rapid rate as the country as whole.

A Few Notes about this Exhibit

The exhibit has been broken into three self-designated categories: Modern Beauties, Moga (modern girls) and Nudes. Within each section, the arrangment of the prints is generally chronological. Information about the artist and the prints are provided when possible.

Most importantly, this exhibit would not be possible without two publications in particular: The Women of Shin Hanga: The Judith and Joseph Barker Collection of Japanese Prints by Kendall H. Brown, Nozomi Naoi, and Allen Hockley, and The Female Image: 20th Century Prints of Japanese Beauties by Hamanaka Shinji, and Amy Reigle Newland. In addition, the two exhibit catalogues by Nihon no Hanga, Feminine Independent: The Modern Women of Pre-war Japanand Emerging from the Bath: The Nude in 20th Century Japanese Prints were integral to my compilation. An interesting aspect about shin hanga prints is that there is a limited repertoire of prints to discuss. As a result, there is quite a bit of overlap in material in all of these sources. However, each provides a unique presentation of similar material through formatting and accompanying text (essays and in-gallery commentary). Therefore the goal of this exhibit is to continue the monumental work that these sources have established, while providing the viewer with a new and unique perspective of the “Female Image” in shin hanga prints.

[1] Christine M. E. Guth, "Japan 1868-1945: Art, Architecture, and National Identity," Art Journal 55, no. 3, Japan 1868-1945: Art, Architecture, and National Identity (October 01, 1996): 16, accessed March 30, 2015, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/777761?ref=no-x-route:5d585089d26556c3f6f0daa02273809d.

[2] Hollis Goodall-Cristante, "Shin-hanga Traditional Prints in a New World," in Shin-hanga: New Prints in Modern Japan, by Kendall H. Brown and Hollis Goodall-Cristante (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1996), 11-30.

[3] Goodall-Cristante, "Shin-hanga Traditional Prints in a New World," in Shin-hanga, 11.

[4] Hamanaka Shinji and Amy Reigle. Newland, The Female Image: 20th Century Prints of Japanese Beauties (Leiden: Hotei, 2003), 10.

Credits

Curated by Olivia Rauss (HC '16)