The Midway: Enacting the Forbidden

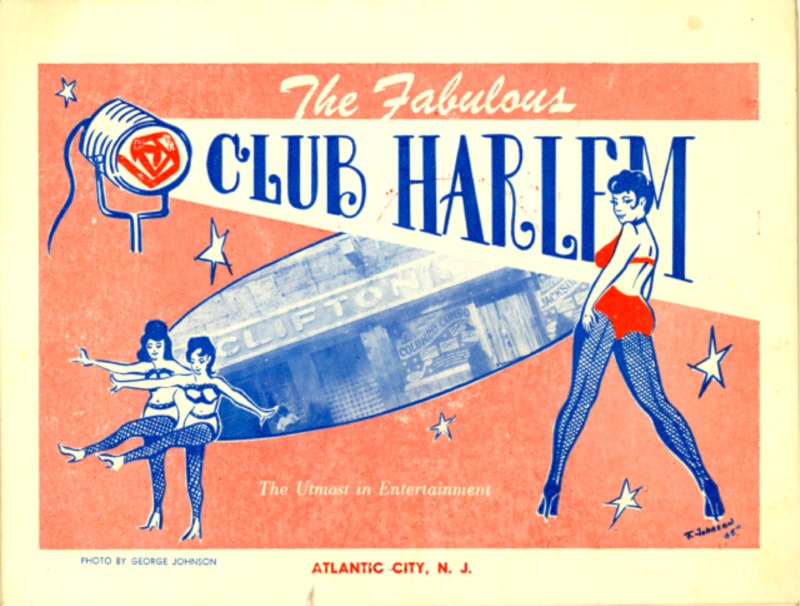

Advertisement for "The Fabulous Club Harlem - The Utmost in Entertainment", ca. 1950-60s

An exotic act in Club Harlem's all-black revue Smart Affairs, 1952

A chorus line dressed as Native Americans, ca. 1950s

Satiating white tourists' appetites for what they believed to be authentically exotic, forbidden, and dangerous experiences, many of the Midway's attractions effectively conveyed convincing illusions of authenticity. Particularly in the case of the Club Harlem, such illusions were predicated upon appropriative and objectifying performances that, rather than crossing and deconstructing socio-racial barriers, tended to reinforce existing notions of white superiority and underscore mechanisms of exclusion.

Empowered by tacit social permission and the selective readjustment of racial barriers, white tourists could cross between two worlds at little to no danger of challenging or discrediting their middle-class propriety, all the while enacting new personas that felt realistic due to the forbidden behaviors and interactions condoned on the Midway. Indeed, just as entertainment venues offered a thrilling transgression of racial boundaries, they also perpetuated race dynamics by reassuring white “slummers that they were welcome on the Northside, that they were safe there, that black performers did not resent them or the racial order, and that there was an easy way back to Atlantic City’s White City.”[1] Artifacts from the Club Harlem's glory days indicate that majority of white tourists daring enough to go slumming in the Northside found exactly the hollow fantasies they were searching for: spectacular interactions with "authentic blackness," erotic encounters with "primitive" peoples, and the freedom to satisfy their curiosities.

The advertisement for "The Fabulous Club Harlem" illuminates the club's marketing strategy and offers indications of how such advertisements correlate with, if not simultaneously draw upon and feed, the desires of white tourists. While featuring bold modern blue and white typefaces set against a rosy pink background, the most effective information is not written but visual. Prominently displayed are illustrations of three chorus girls, wearing high heels, fishnet tights, and bikinis. One of the girls, rendered at nearly twice the scale of the other two, standing alone in the beam of a spotlight wearing a striking, tight red ensemble, seductively glances back at the viewer as if to personally invite them into the club. The notable lack of any address, dates, or times of events may be interpreted as an intentional choice meant to prevent logistics from complicating the pure allure of the club and its performers. Through visual language alone, the advertisement effectively communicates the Club Harlem's sensual floorshows and seems to guarantee viewers intimate, perhaps even physical, interaction with forbidden, sensual women.

An image of African American female dancers confirms that white desire for the exotic and sensual was indeed met once inside the Club Harlem. Captured from over the shoulder of a white male audience member, the photograph depicts at least three women wielding fake swords and dressed in revealing two-piece costumes and matching headdresses. Appropriating a presumably Middle-Eastern cultural tradition, this depiction of a sensual gypsy dance is representative of hundreds of ethnically insensitive acts that constructed illusions of the "exotic" and the "primitive." In reality, the African American dancers only assumed such false alternate personas due to white audiences' desire to do the same, which suggests that tourists initiated the appropriation of Middle-Eastern culture as well as the exploitation of the African American performers themselves.

The same concept may be applied to the photograph of an African American chorus line posing for a formal portrait dressed in faux Native American headdresses and costumes. Again, the costumes and the performers' postures are overtly appropriative of Native American culture and reflect only a thinly veiled attempt to produce an "authentic" experience. If this act featured white dancers, the illusion of primitivism and exoticism would collapse. Clearly, white tourists' conception of authenticity was founded upon superficial standards: as long as performers appeared to fit their on-stage roles, white audiences were satisfied and likely never thought to question a performer's actual ethnicity. Additionally, this latent acceptance of appropriative and inauthentic entertainment highlights the exclusionary nature of white audiences' position of social and racial privilege, one that “sanctioned the bending of social norms and the relaxation of the rigidities of life promulgated by the etiquette books.”[2] Seeking temporary exposure to the primitive and exotic, so too did middle-class tourists implicitly acknowledge the distinction between themselves and the "other," between white and black.