The Boardwalk: Representations of the Commodified Other

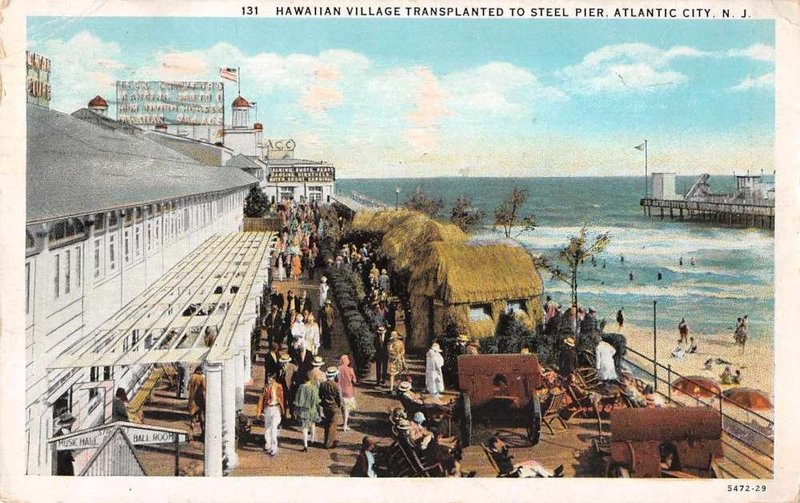

Postcard of Hawaiian Village Transplanted to Steel Pier, ca. 1930s

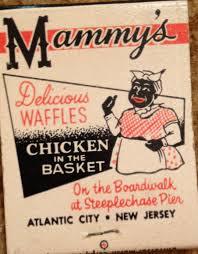

Matchbox advertising Mammy's Delicious Waffles on Steeplechase Pier, ca. 1940s

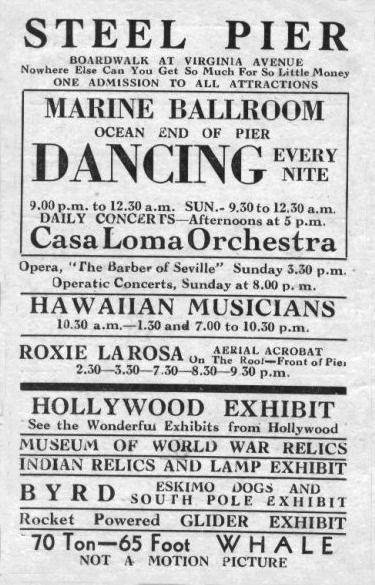

Steel Pier Poster, ca. 1910-20s

Seeking luxurious yet respectable experiences, middle-class tourists often embraced their infrequent vacations to Atlantic City as opportunities to “rise above the masses and to show that they were not ordinary” by enacting, albeit temporarily, fantasies of an upper class life.[1] The Boardwalk was crucial in the construction of these transformative experiences, as its attractions reinforced visitors' desire for “a safe and comfortable place where there was no poverty and where they could show off by imitating the rich."[2] However, analysis of artifacts from the height of the Boardwalk's popularity suggests that many of these diversions were predicated upon and reinforced social hierarchies through appropriative representations of racial and ethnic minorities.

Here, a postcard, matchbox, and poster from various amusements and businesses along the Boardwalk in the early twentieth century articulate both how white audiences' cultural and racial superiority was reinforced through the appropriative commodification of minority populations.

This postcard of a "Hawaiian Village Transplanted to Steel Pier" offers interwoven layers of interpretation. Analyzed internally, i.e. investigating the event as it would have occurred in its historical space and time, the Hawaiian village joined a lineage of ethnic and anthropological exhibits popular throughout fin-de-siècle World's Fairs, carnivals, and other cultural events. Presented during the United States' occupation of Hawaii and decades before the territory obtained statehood in 1959, the immersive exhibit conveyed an “imperialist nostalgia”[3] and offered audiences a seemingly "authentic" fragment of an exotic land, which effectively reduced Hawaiian culture to fit within a commercialized sideshow. Subjected to the gaze of white audiences, the exhibit's not-so-subtle imperialist undertones conveyed a sense of racial hierarchy and cultural superiority, sentiments that the postcard disseminated wherever it was sent.

The matchbox advertising "Mammy's Delicious Waffles" magnifies the overt racialization of Boardwalk entertainment. Depicting a satirized caricature of a grinning, buxom African American woman, the matchbox blatantly connotes black servitude. The name of the restaurant gives little indication of any social or racial conscience, as "Mammy" is a historically derogatory term referring to a black nurse or nanny employed by a white family. Indeed, most tourists likely had no candid interracial interactions, as “white city leaders tried to govern – even narrate – every black-white encounter in the city.”[4] Thus, the racialized image on the cover of the matchbox no doubt skewed and restricted patrons’ conception of black women, if not all African Americans, to one of happy servants perpetually catering to white needs.

Continuing the argument of appropriative entertainment as a means of cultural affirmation on the Atlantic City Boardwalk, a poster from the Steel Pier contributes an unmistakable glimpse of the many forms of exotic entertainment that reified visitors' cultural superiority. Promising that "nowhere else can you see so much for so little money," featured on this poster alone are multiple daredevil and acrobatic performances; Hispanic and Hawaiian musical acts; operatic concerts; a museum of World War I relics and Indian artifacts; Eskimo dogs and a South Pole exhibit; and a 70-ton 65-foot whale. However, most prominently displayed is the formal dance offered each night in the Marine Ballroom. Juxtaposing such dances with nearly any other amusement at the Steel Pier demonstrates how “racial distinctions muted social differences among whites and sanctified European Americans as respectable.”[5]

[1] Simon, Boardwalk of Dreams, 41.

[2] Ibid., 19-20.

[3] Knight, “A Climate for Health and Wealth,” 51.

[4] Simon, Boardwalk of Dreams, 39.

[5] Jon Sterngass, “The Rise of Coney Island: Strangers in the Land of Perpetual Fete,” in First Resorts: Pursing Pleasure at Saratoga Springs, Newport & Coney Island, (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001), 109.