Japanese Modernism Across Media

Ainu Culture from Meiji Restoration to Present Day

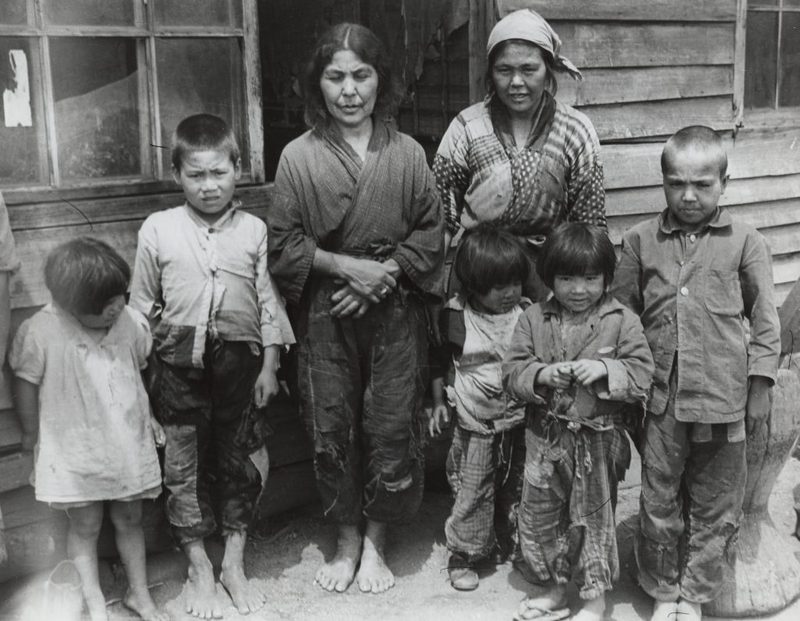

With the Meiji Restoration in 1868, the Japanese government was officially in control of Hokkaido as a part of Japan. In 1899, an act in the name of protecting these indigenous people, Hokkaido Former Aborigenes Act, was passed by the Japanese government. However, it entailed banning the use of the Ainu language, banning traditional ceremonies, the Japanese government taking control over the land the Ainu had in possession, adopting a new Japanese name to go by, and the prohibition of the Ainu from fishing and hunting. Although mistreatment by the Japanese people and the government existed before this act, this act was a "legal" and "official" way for the Japanese government to take away the identity of the Ainu.

Through the wartimes and into the present, Ainu people faced discrimination in schools, work places, and the society itself, as they struggled to adjust to the new, Japanese way. It did not take them very long to think of the Ainu identity as shameful and embarrassing. Many Ainu people married Japanese people to "lessen" the Ainu blood in their children, and told their children to do so as well.

So are there present day Ainu people? What do they do and what do they look like?

Present day Ainu live as Japanese citizens, with their population mainly clustered in Hokkaido and Tokyo. Most people cannot tell the difference between a Japanese person and an Ainu person, as they live no differently from the Japanese. While some make a living in a workplace completely unrelated to their identity, Some people decide to be heavily involved in their traditions and work in the tourism industry or with traditional crafts. Others become musicians, actors, and artists to express their identity. Others become writers or professors, working in academia to educate more people about themselves.

Haruo Suzaki

Born in Osaka. He moved to Hokkaido at the age of 19, worked under Tadashi Kaizawa deputy chairman of the former Hokkaido Utari Association, and started woodcarving at the age of 24. He fuses bold, powerful carving with delicate Ainu patterns to create works that are redolent of the unique world of Haruo Suzaki. Particularly sublime are items such as the iku-supai (prayer stick) and tuki (cup), implements used to convey prayers to the kamuy (god). Also popular are his walnut coasters and nima (bowls), which bring out the beauty of the wood's grain. Haruo Suzaki's passsion for his craft imbues each one of his handmade implements.

(Description from Nibutani Ainu Takumi no Michi)

Toru Kaizawa

Born in Nibutani in 1958, he grew up in the company of his craftsman father (Tsutomu) and his fellow artisans. His great-grandfather, Utorentoku Kaizawa was one of the two artisans renowned for their skill in the Meiji Era. Whilst valuing the traditions inherited from his great-grandfather, he melds into them his unique sensibility and techniques, energetically grappling with the creation of original Ainu art that expresses his own personality and message. Flashes of inspiration provide the subjects for his works. The idea for his famous 'UKUOKU/ The Round" came from a photograph of a woman's arm with an ancient Ainu tattoo, and was created with the message that culture is passed down through the generations. He has won many prizes, including the Hokkaido Governor's Award at the Hokkaido Ainu Traditional Craft Exhibition. He is the owner of Kita no Kobo Tsutomu.

(Description from Nibutani Ainu Takumi no Michi)

Koji Kaizawa

Born in Nibutani, Biratori in 1962. He started woodcarving while helping out in the folk art shop run by his father (Tsutomu), and in 1992 he was awarded First Prize at the Hokkaido Ainu Craft Exhibition. Since then he has won many other prizes, including the Hokkaido Governor's Award. In 2009 The Foundation for Research and Promotion of Ainu Culture recognized him as a traditional craftsman. He is well-known to love fishing and fish so much that he says he cannot create good carvings unless he has been fishing. He says that when he holds a fish in his hands it teaches him how it to carve its form, and that his greatest wish is to "carve fish that seem to be alive". In addition to his fish motif he produces a wide variety of traditional Ainu craft items, and is actively working on creating new items, such as bandanas with a salmon design. He is the owner of Tsutomu Mingei.

(Description from Nibutani Ainu Takumi no Michi)

Shigehiro Takano

Born in Tokyo. While travelling in his 20s he happened to drop by Nibutani and was fascinated by the beautiful woodcarvings. Drawn by the warmth of its people, he decided that this was where he wanted to live and moved to Nibutani. In 1972 he started to learn his craft from the woodcarver Moriyuki Kaizawa. He finished his apprenticeship in 1979 and established Takano Mingei in 1980. He is profoundly loyal to traditional Ainu handicrafts and designs, and devotes himself to producing ita (trays), nima (bowls) and makiri (knives) whilst studying the designs of skilled artisans. In particular, Shigehiro Takano is the only person in Nibutani today who has mastered the precious techniques required to make the tonkori, a traditional five-stringed instrument that has been handed down in Ainu culture. He holds solo exhibitions throughout Japan and works hard to publicize the charms of Ainu crafts. He has won many prizes, including the Governor's Award for Excellence at the All-Hokkaido Ainu Folk Crafts Contest. He is the owner of Takano Mingei.

(Description from Nibutani Ainu Takumi no Michi)

Akiko Hiramura

She embroiders traditional Ainu patterns, focusing intently on carefully completing each individual stitch so that each chainstitch is exactly the same size. She is also meticulous in the beautiful finish that she gives to the corners, known as kirau, and visitors are fascinated by the level of perfection of her painstakingly crafted works. When she makes kimono she attaches a cloth with a pattern called kirifuse and embroiders over that. She enjoys the process as the pattern takes shape and becomes engrossed in her work, losing all track of time. Small items such as her coasters, luncheon mats and pouches, sewn with brightly-colored thread, are also popular. It delights her that the people who select them will value them and use them well. She was awarded an Honorable Mention by the Hokkaido Utari Association at the Hokkaido Ainu Traditional Craft Exhibition for a karakarape (kimono) on which she worked for seven months.

(Description from Nibutani Ainu Takumi no Michi)