Japanese Modernism Across Media

The Birth of Gutai

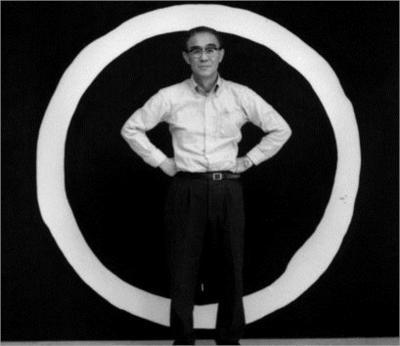

The Gutai Group rests on pushing artists to find new ways to extend the boundaries of art. This philosophy was established by the group’s founder, Yoshihara Jiro. Yoshihara did not come up with this philosophy out of nowhere; it was instead a response to the limitations the powerful Western art community gave to Japanese artists. Power figures from this region accused most Japanese modern art as being imitations of Western art. Japanese modern artists, who were able to see the flourish of traditional Japanese art styles, needed to find a way to prove their worth as artists to the global art community. Yoshihara Jiro, a trained painter, was accustomed to this reality as a young artist. The harsh reality of the view international artists had towards Japanese artists contrasted directly with the worldview Yoshihara had established.

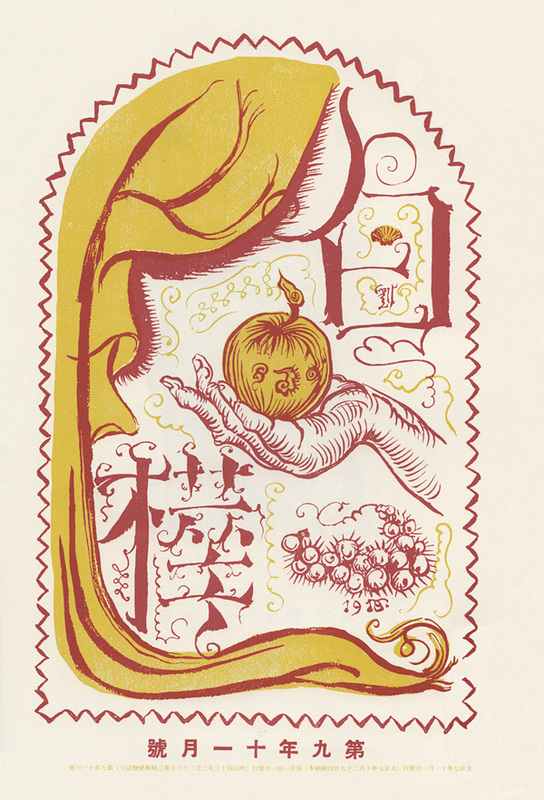

As a young artist, Yoshihara read internationally circulated print media that exposed him to a visually transnational art community. The magazine most noted for influencing Yoshihara was Shirakaba. This magazine, which circulated during the Taisho period (1912-1926), included replications of art created by modernist artists such as Van Gogh and Cezanne, as well as essays from a variety of artists. The magazine’s circulation allowed for a transnational community to emerge in the eyes of a young Yoshihara. The magazine made it appear that artists, no matter where they may reside, could communicate with one another in the goal of building discourse and spreading ideas about their artistic ways. (Tiampo, “What has never been done before!” article, 692).

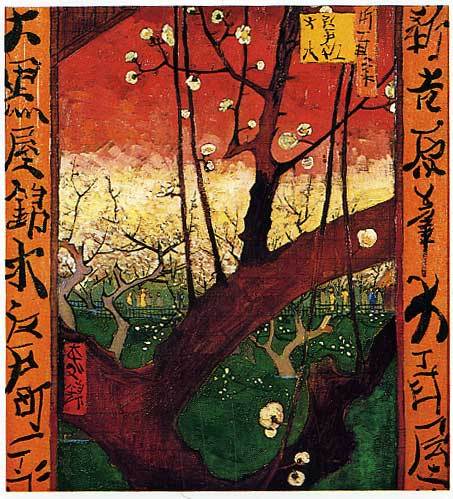

The articles from these magazines were not afraid to critique the happenings at the time. For this reason, power relations could easily be exposed that revealed the highly-circulated opinion that Japanese modernist painters simply copy their Western counterparts, instead of a discourse that suggests they are influenced by these artists. The latter was typically applied to artists from Western countries, who included themes often seen in Japanese traditional art. Their art, instead of being viewed as a “copy” was praised for it’s originality. In response to Van Gogh’s Japonaiserie paintings, art historian Marijke de Groot said, “there is no question of a slavish copy. It is more a personal transcription in which the colors are intensified and the focus has shifted to the landscape because Van Gogh has omitted the cartouches.” Another art scholar was even cited as saying “it could be said that his copies appear more Japanese than their Japanese models” (Gutai: Decentering Modernism, 17). The climate from this timeperiod was unmistakably one that placed Western art above Japanese art.

Yoshihara experienced this difficult climate first hand. His work was deemed unoriginal by critiques during his exhibition in 1928. This came as a shock to Yoshihara. The obvious difference between how Western artists work was interpreted in comparison to how Japanese artists became apparent to Yoshihara. Years later in 1954, to find a name for himself and Japanese artists with a similar idea of creating abstract art that pushed the bounds of art, Yoshihara established the Gutai group.