Japanese Modernism Across Media

The Museum Effect on Radical Pieces (Visual Essay)

"The radically inventive and influential Japanese art collective yielded one of the most important international avant-garde movements to emerge after World War II. Based on fifteen years of research, Gutai: Splendid Playground provides a critical examination of both iconic and lesser-known examples of the collective's dynamic output over its two-decade history and explores the full spectrum of Gutai’s creative production: painting, performance, installation art, sound art, experimental film, kinetic art, light art, and environment art."

-Jen Carlson, "The Gothamist" Journalist

Guggenheim’s “Splendid Playground” and Original Installation

Museums, cafes, small galleries, parks, and alleys – all places a piece of art may be displayed at, and all carry very different meanings from the respective institutions, or lack thereof. Artists involved in the Gutai group, founded in 1954, understood the various ways these locations would impact the way in which audiences would interpret and consume there artwork, and throughout the almost 20 year run of this group would take these understandings to serious consideration when deciding how their artwork would be displayed. The group strategically held exhibitions in various locations, ranging from public parks where access to artwork was open throughout the day and night, to department stores, to the open sky above Osaka. Where their artwork was displayed effected how audiences interacted with the pieces, as well as changed how people interpreted them. From this perspective, it is important to analyze the Guggenheim Museum’s intricate display of over 100 creations and recreations from the Gutai group during the 2013 exhibition “Gutai: Splendid Playground”. Incorporating images into this essay, I will analyze the Guggenheim’s display of Gutai artwork, taking into carful consideration the differences between the Guggenheim’s display practices to the original Gutai artwork. I will also look at the innovative practices the Guggenheim utilized to reinterpret and resituate Gutai art and the goals of this group in the modern context.

Emergence of Gutai

During the tumultuous postwar period, painter and businessman Yoshihara Jiro formed the Gutai group. Yoshihara embarked on the journey of creating a modernist Japanese art collective whose driving phrase was “create what has never been done!”. With this motto, the artists in this group set out to bend the rules of art and experiment with materials in new and interesting ways. But this goal was more than just a hope to create something cool; it arose from the reality that Japanese modern art was rarely taken seriously by the broader art community. Yoshihara experienced this harsh reality as a young painter[i], and sought out years later to develop a community that was able to go against the Euro-Centric notions of creativity in art by expanding the very definition of art. The group even went so far as to make popular the word “e” to describe artwork, a symbol for the future ability of this group to bend definitions typically thought to be stringent.

The goals of the Gutai group can be best summarized with the assistance of the 1956 publication “The Gutai Manifesto”. Yoshihara published this piece in the Gutai group’s self-titled magazine, which sought to have their art reach those who may not be able to see pieces in person. Some of the main goals declared in the manifesto include bringing emphasis to life and the spirit in matter, creating a new art form that separated itself from other established art movements while still being influenced by and interacting with a transnational art community, create pure art, not having any rules when creating art, and pushing the bounds of what art could be. In this way, the Gutai group was attempting to prove art critics wrong who cited Gutai works, and the broader non-Western art world, as being derived from Western modern art[ii]. Yoshihara’s most famous quote, which was reported to have been told to all Gutai artists, asked for artists to, “create what has never been done before!”.[iii] This phrase is more than just a want to see something new; it instead seeks to find a way to go against the art world’s limited perspective.

The ideology of creating work that had never been done before ran through the current of the Gutai group’s various creations and installments. In combination with this idea, the Gutai group also emphasized rethinking how art should interact with viewers. Gutai members, especially early members, had a fascination with children’s artwork. The ability for this artwork to interact with a wide audience by breaking down walls inspired Gutai artists to not only create their own children’s journal and lead art classes to these young people, but to also create installations that both invited and forced audiences to interact with pieces in non-traditional manners. In the Gutai group’s first outdoor exhibition, all work on display counteracted the museums that imposed strict codes of conduct on museumgoers. The physical walls were broken down, allowing for a more free-flowing creative expression to emerge and permeate itself in the audience membership. In the following section, I will analyze the ways in which the Guggenheim Museum attempted to install Gutai works that arose from outdoor exhibitions in an indoor space.

Fig 1. Work (Water) by Motonaga Sadamasa, original 1956 installation at Ashiya Park, Ashiya, Japan

Fig. 2. Work (Water) by Motonaga Sadamasa, 2010-2011 installation at Museo Cantonale d’Arte, Lugano

Guggenheim Interpretation and Implementation of Gutai Artwork

During “Gutai: Splendid Playground”, the Guggenheim museum emphasized an attempt at re-creating the essence of the Gutai group’s original exhibitions during the museum-wide displays of Gutai art. This lead to various objects on display that encouraged thorough audience interactions and reinterpretations of artwork and display practices for the 21st century audience. In this section, I will analyze and interpret the different display practices based upon written accounts, theories about Gutai art, and my personal opinions. It should be noted, though, that while I have performed extensive research on the Gutai group and the Guggenheim’s museum exhibition of this important art circle, I never saw with my own eyes these displays. I will compare original exhibits with the Guggenheim’s reinterpretations, as well as explore facets of the Guggenheim’s exhibition that allowed for the goals of the Gutai group to be achieved in the modern context. My interpretations of installations will draw heavily from the ideas of the “museum effect” as described by Svetlana Alpers, and the opposite “playground effect” that I believe encompasses the Gutai group’s various pieces.

The museum effect is present in most spaces that are dedicated to the display of art or pieces deemed as “art”, especially spaces that are intended for a public audience to view. In Svetlana Alpers’ article “The Museum is a Way of Seeing”, she argues that the museum effect is a mode of seeing things. Viewers are encouraged by display set-ups to gaze at the details of objects, to not touch, and to contemplate silently the object that is in front of them[iv]. The museum, according to Alpers, best encourages this mode of thinking. This in turn results in a ritualized mode of attending museums, where museumgoers are encouraged to look, to not touch, to contemplate silently, and to not disturb the state that objects on display are at in the current moment.

In somewhat of a contrast to Alpers’ museum effect, I believe there is room for theory to build on the opposite of this mode of thinking. With this intention, I propose the concept of a “playground effect”. This effect embodies the idea of going to a playground – people are encouraged to interact physically with works. This physical element is essential to the viewers experience at the playground, and through the physical actions a fun experience is achieved. Through this fun experience that incorporated both mental and physical aspects, participants may reflect upon what is around them and become engaged in this process.

Based on the Gutai group’s manifesto and various writings that described the goals of the group, it appears that viewers were supposed to feel a sense of a “playground effect”. Viewers, especially those who did not necessarily fall within the category of artist, were encouraged to interact with art in new, sometimes unusual ways in order to feel matter and experience the spirit of life through the medium. Creativity and the degree of accessibility presented in objects were at the core of the goals from the Gutai group. Original exhibitions of Gutai artwork embodied these elements, and display practices created open atmospheres for viewers of various levels of familiarity with art.

At the Gutai group’s first and second outdoor exhibitions, works were intermingled with the natural surroundings of the pine wood environment in Ashiya, Japan. The exhibition “hall” was open throughout the day and night, and the idea of physically interacting with art was extremely apparent. One of the most well known from the second outdoor exhibition was Motonaga Sadamasa’s “Work (water)” in 1956 (figure 1) during the second Gutai-run outdoor exhibition.

The installation used tubes of plastic strung from tree to tree with different colored water, dyed by ink, inside of them. Colors were described as including reds, blues, yellows, and mixtures of these primary colors. Many of the tubes of plastic were in reach of exhibition goers, allowing for people to physically interact with the installation. Water was able to shift and change depending on the degree to which someone would touch the tubes of plastic. The piece therefore changed depending on who was visiting, and how interested these various visitors were in interacting with the installation. Kids were able to interact with these pieces through touch to create an experience that they could physically shape. Additionally, the piece not only changed depending on people’s physical interaction; the natural environment also affected the way the tubes of water could be seen. The colors in the tube would change depending on the cloudiness of the sky or by how rays of light hit the tubes. If wind blew, the tubes would move and create an experience that could evoke feelings of transformation within viewers. The installation of “Work (Water)” relied on the natural elements and reactions from the exhibition goers. Museum goers did not have an experience shaped by the museum effect as described by Alpers, but instead were free to physically engage with the artwork however they saw fit, which goes in line with the “playground effect”. Using various senses to engage with the piece was encouraged, as the literal elimination of walls allowed for the exhibit to be one that encouraged audience interaction, as well as interaction with environmental forces. This piece, as with many other Gutai works, did not fear change; instead it embraced it as an opportunity to reveal creativity in a new manner. Figure 2 provides a glimpse into what visiting the outdoor exhibition would have felt like; being able to walk outside, nature around you, to gaze up at splendid colors almost floating above you. The image is able to do this in perhaps a better way than figure 1, which is a photograph of the original exhibition, because of the use of colors in figure 2.

As figures 1 and 2 reveal, the interactivity with both the environmental space and people allowed for an experience that allows for and encourages physical engagement that is not present at museums. Although figure 2 shows a museum showcasing “Work (water)” in a setting similar to the original pine forest, the Guggenheim’s Splendid Playground exhibition chose to instead incorporate this iconic piece in the middle section of the museum. Motonaga himself, who completed the designs for the Guggenheim up until his death, reconfigured the piece to the museum’s unique setting[v]. As figure 3 shows, Motonaga’s decision to replicate “Work (water)” continued to allow the sun to play with the colors through the open ceiling above. However, this decision also left the motion of the tubes to be rarely transformed by neither natural elements nor visitors touch. The tubes of plastic were strategically stationed far away from the arms of museumgoers. Children could not innocently play with these pieces as they had at the Outdoor exhibition in 1956, and the water would, in theory, stay in the same place for almost the entire duration of the museums installation. Furthermore, the removal of the outdoor aspect of this piece would not allow for natural elements, such as rain or wind, to effect how the piece would be viewed.

Motonaga’s approach to this work is very different than the original exhibition. Instead of an interactive piece that is constantly changing, a more stationary approach is indeed taken. With this, the Guggenheim reinforced a museum effect on “Work (water)”. Seeing, not feeling, was a rule that museumgoers had to obey. The privileging of the material at its current state was also enforced through the absence of interacting with the tubes by both viewers and nature. This privileging of materials was further elevated because of the literal elevation of the tubes of water. One art critique stated that it allowed for viewers to see the tubes as a spiritualized element. They saw this as a metaphor for the Gutai group’s ascent to critical art fame, as “viewers cast their gaze to the heavens, as though in awe of Gutai’s rise from obscurity to recent claims that it was the most influential postwar Japanese art movement”[vi]. While these comments are just, they allude to an extremely similar mode of engagement that the museum effect requires of individuals. The gazer can never feel what they admire, and must instead rely solely on their eyes to engage with the object and feel it’s impact. Though Motonaga, an esteemed Gutai member, designed how his work would be seen in the Guggenheim, I do not believe this installation completely embodied the goals of the Gutai group. The Gutai group, as I mentioned previously, articulated a strong urge for modern artists to move away from traditional modes of communicating art. This should be interpreted as moving away, additionally, from the traditional modes of engaging with art in museum contexts. The original installation of “Work (water)” found a way to engage with art in a new manner through the use of the outdoors, trees, and being accessible to the physical bodies of viewers. The Guggenheim museum did not allow any of this. Viewers needed to instead interact with the piece as they would any painting: by gazing and not touching.

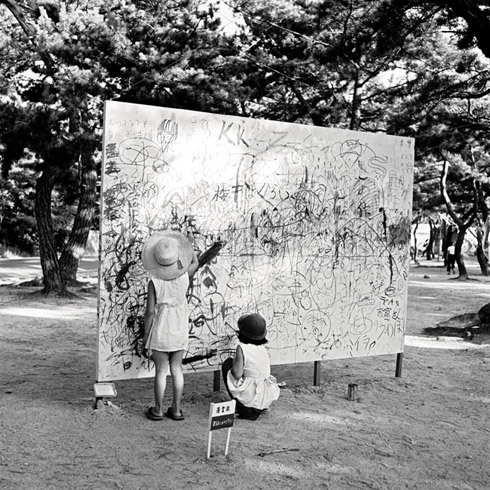

Fig. 4. “Please Draw Freely” by Yoshihara Jiro, original installation, 1956

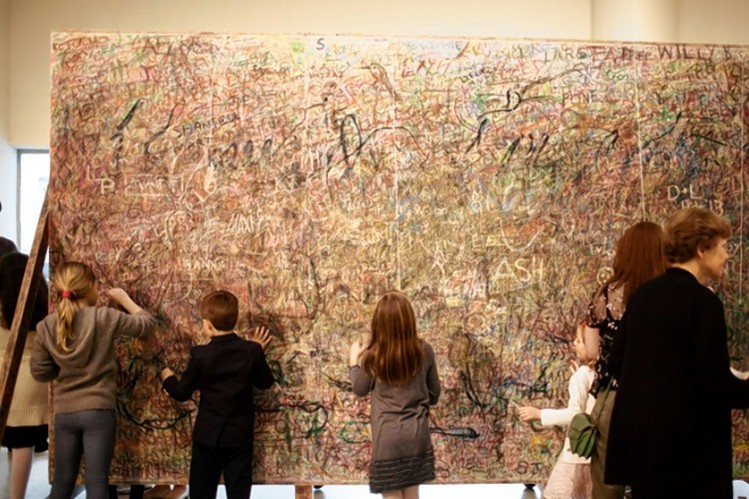

Fig. 5. "Please Draw Freely" by Yoshihara Jiro, Guggenheim Museum's "Splendid Playground" installation, 2013

Though the installation of Motonaga’s “Work (Water)” was unable to create a similar mode of experience as the original exhibition, the Guggenheim’s interpretation of Gutai founder Yoshihara Jiro’s “Please Draw Freely” was able to not only mimic the original piece, but took steps to create an online platform to fit with current trends of social networking that defines young generations. Yoshihara’s “Please Draw Freely” was first installed in 1956 at the second Outdoor Gutai Art Exhibition in Ashiya, Japan. The installment I analyzed previously, “Work (water)” appeared at this same exhibition. Many similarities were apparent from these two works. They both urged viewers to participate in the artistic process and changed with time because of the various factors that interacted with the installations.

As the title “Please Draw Freely” suggests, the purpose of this work, which consisted of a large white board with a sign simply saying “Please Draw Freely”, provided tools for viewers to draw as they saw fit on the board. In the original 1956 installment, the board was placed outside, allowing not only participants to change the work but also for natural elements as well. The work was extremely accessible, as the work was low to the ground and tools were provided to draw upon the surface. The “playground effect” is demonstrated through the forward invitation for viewers to interact directly in their own creative manner to distort, change, and shift the board presented to them. By being outside, participants may have felt an increased sense of freedom as the act of drawing was not limited to an indoor setting, but instead was taken outside.

Shifting gears to consider the Guggenheim’s implementation of this work should be analyzed at two levels: the indoor display and the interactive website. The first involves the physical implementation of “Please Draw Freely” that was at the beginning of the exhibition. Museumgoers are presented with various writing utensils, and are even encouraged to use whatever they have on hand to add to this piece. The actual Guggenheim’ installation was refabricated many times in order to allow for more room for people to draw upon. Just like the original installation, people of all ages were encouraged to participate. The strict bounds of the museum space, though the area in which this piece was situated in, did not impose itself too much on this section. People could feel a playground effect. Creativity and participation were highly encouraged, and the art appeared extremely similar in terms of practice and display as the original installation. The second aspect to consider is the online counterpart titled “Please Draw Freely”. This website describes itself as being a place for people to engage with the ideals of the Gutai group through a new interpretation of the original “Please Draw Freely”. The collaborative process was emphasized in this setting, and the website encouraged “visitors to draw with people from around the world”[vii]. Sadly the website portion of this exhibit is closed to submissions, however viewing the site is still permitted. It appears members were able to build upon other people’s works in order to create original digital drawings. Not only does this website embody the “playground effect”, but it does so in a manner that fits the modern day as well as deepens the understanding of the Gutai group. This last part, I believe, not only encompasses the idea of collaborative creative expression, but also the idea of a transnational art community. The Internet facilitates the interaction of artists, especially those who may not consider themselves to be “artists” to interact with one another in a creative expression, just as they would in the offline “Please Draw Freely” installation.

Conclusion

The Guggenheim’s “Splendid Playground” exhibit was an amazing opportunity to view over 100 Gutai works, and to be able to interact with them in a manner reminiscent of the original installations. The difficulty of placing these works in a space unintended for a museum setting sometimes made for maintaining the original essence difficult. This was apparent in the 2013 rendition of “Work (water)” (1956), which took away the interactive component of the revolutionary installation. Yet for other works, the Guggenheim museum was able to place works in modern contexts to continue to exude the original intent of the works. The artwork “Please Draw Freely” (1956) was re-envisioned in a manner that allowed folks to collaboratively create a piece of art, not only in the offline but also on the more transnational online world. The Guggenheim museum shows a trend of being unafraid to use free technologies in order to enhance the museum experience. The “Please Draw Freely” online website reveals this, as does the interactive phone application that allows interested viewers from around the world to be able to consume the museums’ exhibits, both past and present. Though I was only able to delve into detail on comparing two Gutai display practices, I believe there is a message to be taken away from the Guggenheim’s installations. While mimicking the original displays is important, the use of technology to further enhance experiences can allow for viewers to feel more connected to pieces, as well as attain the goals of the transnational art community, which the Gutai group sought to interact with. Museums should therefore not be afraid of such technologies, and envision using them in their own reinterpretations of work from year’s past. From this perspective, museums may be able to reach a broader audience than if they had stuck to tried-and-true methods of displaying art. Through this, the art community will grow, and more artists may possibly emerge whom, like Yoshihara Jiro, wish to “create what has never been done before”.

[i] Ming Tiampo, “ ‘Create what has never been done before!’ Historicizing Gutai Discourse

of Originality” Third Text, 21:6 (2007): 693

[ii] Bruce Altshuler, “To Challenge the Sun: Exhibitions of the Gutai Art Association” The

Avant-garde in Exhibition (1994): 184

[iii] Ming Tiampo, “ ‘Create what has never been done before!’”: 693

[iv] Svetlana Alpers, “The Museum as a Way of Seeing” Exhibiting Cultures (1991): 27

[v] Guggenheim website, “Play: And Uninhibited Act”, http://web.guggenheim.org/exhibitions/gutai/ ,copyright 2013

[vi] Namiko Kunimoto, "Gutai's Ascent." Art Journal 72, no. 2 (2013): 114.

[vii] Guggenheim Museum, http://web.guggenheim.org/exhibitions/gutai/draw/, copyright 2013