Journals

Journal writing today is an intimate act, allowing one to understand the self through the processes of writing and reading about his or her life. During the eighteenth-century, the intentions behind journal writing were different from what they are today (Imbarrato 1-2). Autobiographical writing in colonial America taught others how to live morally by example and encouraged commuinity conformity. Around the turn of the century, the perceived purpose of diary keeping was changing: writing about the self allowed one to better examine his or her own actions and impact on the world.

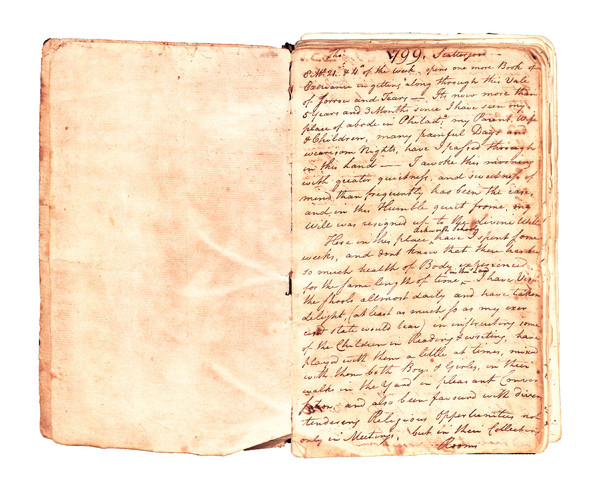

The journals of Thomas Scattergood reflect motivations behind both seventeenth and eighteenth-century diary writing. One of his goals certainly was to promote faithful adherence to Quaker standards. However, it is also clear that Scattergood’s writing is deeply personal as he supplicates and seeks inner peace. His earliest journals, written long before his time in England, do little more than serve as a travel record: they document where he went, who he stayed with, and which meetings he attended. In his journals from England he recorded more in his entries, particularly about his spiritual state.

These pages make up the first entry in a new journal for Scattergood. What one notices immediately is the agonized tone and emphasis on the duration of his travels in England thus far––five years, three months. The reader is compelled to be conscious of the journal's time span, an aspect that is at times overlooked when a day's entry can be read in a minute. One must take certain contextual elements into account while reading these passages. For instance, Quaker ministers kept records of their physical and spiritual journeys in order to provide their Meetings of Elders and Ministers with documentation of their labor. Consequently, Scattergood’s writing cannot be completely separated from community conformity and appealing to his audience.

On the other hand, journals allow one to record time spent, to select moments and details to be thought over and revisted. Time is a point of focus for Scattergood in his journals from abroad; he questions whether or not it has been wasted, wonders how much longer he will be compelled to stay, and wrestles with the ever-increasing distance he feels from his family. In a year’s time, he will set sail for the United States again. While he may be painfully aware of his long separation from home, Scattergood is not yet ready to leave.

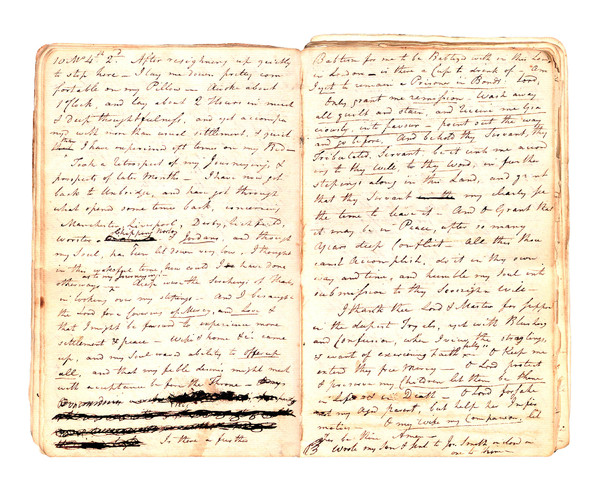

In this unusually long entry, Scattergood records the act of reading over his own journals. This process of writing about earlier entries is a process of self-evaluation and re-affirmation. His approval is reinforced in his expression of dissatisfaction and intense scrutiny: "and though my Soul has been let down very low, how could I have done otherways as to my Journeyings..." This passage is especially emphatic with underlined sentences and several lines crossed out. Both his present and past self is undergoing a process of revision and accentuation.

Scattergood also recommits himself in writing to God: "Wife & home & ch[ildren] came up, and my Soul craved ability to offer up all, and that my feeble desires might meet with acceptance before the Throne..." As he remembers his wife, children, and home Scattergood yearns to proffer them up to God--an act of devoutness that many pious biblical figures undertake.

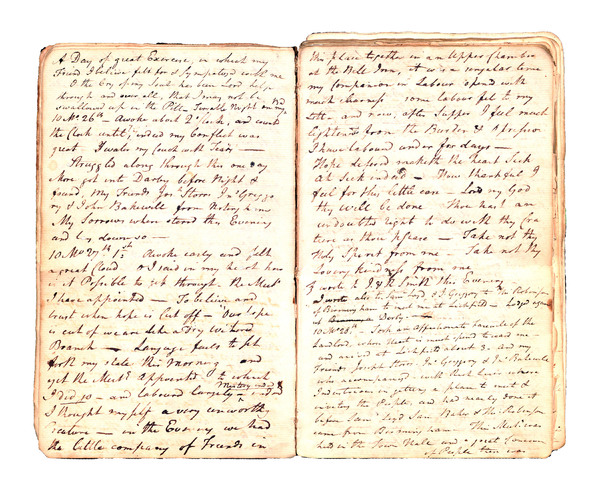

Another important element to keep in mind is that Scattergood inscribed a melancholic tone into his journals. This may pose a difficulty in distinguishing between his spiritual writing and melancholy. The formulaic, repetitive writing of spiritual documentation is quite alike to this description of writing with depression: “We spend for ever talking and thinking around the same cycles of worry and self-doubt without really saying anything, and certainly never reaching conclusion or capturing in words the essence of what is in perpetual motion within us....Even language itself proves a false friend, offering explanation and analysis, delivering instead grammatical evasion and circumlocution," (Ingram, 8). Though melancholy and depression do not have the same meanings, they represent similar thoughts and moods to each other.

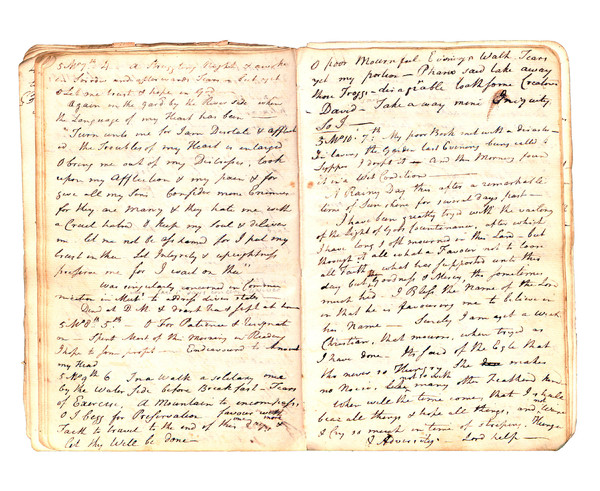

In the entry from 5/7/1800, Scattergood records, "the Language of [his] Heart." This phrase comes up in other entries and indicates a moment of spiritual feeling manifested as a phrase or quotation. The passage indicates a state of desolation and implorement for deliverance. A few days later, his entry on the 10th remarks upon the rainy weather after a few precious days of sun, collocating his closedness--"the vailing of the Light of Gods Countinance"--with the weather. In other passages, the gray weather of London can put Scattergood into a dismal mood. However despite the low condition of his mood, he remembers to be thankful for not having completely lost faith. He uses an aphorism of the eagle to remind himself to remain stoic to pain: "Its said of the Eagle that tho never so Hungry She makes no Noise, not so with many other Feathered kind." While Scattergood calls himself a "weak Christian," he uses the image of the stoic bird as a model to emulate.