Please Touch: The Display of Native American Children at the AYP Expo

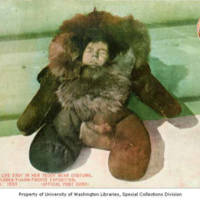

An "Eskimo" baby in a fur outfit. Caption on image: "'Raltugia' takes life easy in her teddy bear costume. Eskimo village, Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition. Seattle, Wash. 1909."

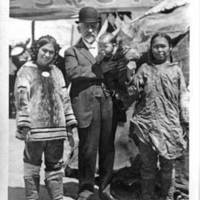

Dr. Frederick W. Seward posed with two Eskimo women and child, Pay Streak, Alaska Yukon Pacific Exposition, Seattle, 1909. The label reads: "Dr. Frederick W. Seward, son of William H. Seward, was a chief figure in the purchase of Alaska. Eskimos left to right: 'Columbia', Eskimo from Labrador; infant named 'Seattle'; and mother of the child."

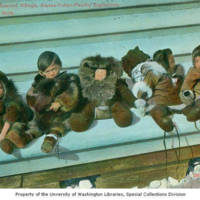

Native Peoples in living displays is one of the difficult subjects of early American expositions. Obvious indignities aside, in some situations they were treated cruelly, inhumanely, outrageously, shamefully. That being said, they were nevertheless a very visible part of the AYP Expo, and a fascination to visitors. They were an important part of the certification of the fair itself, as the AYP Expo was celebrating the annexation of "Eskimo" land and people. Any controversy over them tended towards protection of the visitors; their display was not only otherwise generally acceptable but helped to establish the educational credentials of the Pay Streak. Fairgoers were presented with active displays of craft production, domestic life, dance, clothing and war, but whether or not they actually learnt anything from the experience is up for interpretation. For sure, white fairgoers viewed the Native Peoples from paternalistic and imperialistic podia.

The AYP Expo's way of displaying Native American babies further emphasizes the patronizing and hegemonic biases that white America applied to non-Anglo-Saxon peoples. While the largely white newborns were housed safely behind glass and barriers, the Native American children were literally offered to dozens of visitors to touch and hold, setting their safety aside for the fairgoer's enjoyment and "education." Lisa Blee writes of this in her article, "'I Came Voluntarily to Work, Sing, and Dance': Stories From the Eskimo Village at the 1909 Alaskan-Yukon-Pacific Exposition":

"Columbia and Seattle became the darlings of exposition promoters. Baby Seattle appeared in at least one published photograph, and Columbia be came perhaps the most photographed Inuit woman of the era. Certainly both babies received lavish attention from the press, and interested crowds followed every gurgle and smile. This stream of strangers, because they carried a variety of microbes, may also be the reason so few native babies born at fairs survived. There is no evidence that participants in the Eskimo Village lacked food and appropriate shelter, but newborns there were especially vulnerable to disease. In an era when infant mortality was already high, these babies were subjected to contact with thousands of visitors— some from far-off places—without the protection of fully formed immune systems. It appears that visitors were even encouraged to handle the newborns on display. A Siberian Yupik newborn died of bronchitis in Santa Rosa during the group's western tour, and at least two other babies in Columbia's cohort died in Chicago. And, unfortunately, Baby Seattle succumbed to illness on the very day his parents boarded a schooner to return to Siberia at the close of the exposition. Notably, the newspapers reported the dead infant's name as Raltugie, perhaps acknowledging the family's additional name for the child and certainly hoping to avoid the obvious symbolism in the tragic end of the city's mascot" (Blee 135).

Blee, Lisa. "'I Came Voluntarily to Work, Sing, and Dance': Stories From the Eskimo Village at the 1909 Alaskan-Yukon-Pacific Exposition," The Pacific Northwest Quarterly, Vol 101, No ¾, Race and Empire at the Fair (summer/Fall 2010), p. 126-139.