Japanese Modernism Across Media

Visual Essay: Yoshitomo Nara's "The Lonesome Puppy"

Yoshitomo Nara (1959-) is a popular and influential Japanese contemporary artist who grew up during post- Pacific War Japan. He channels memories of his lonely post-war childhood into his paintings and sculptures, causing his mostly adult audience to revisit memories of their own childhoods. Although he is most famous for his rather dark depictions of rebellious little girls, he has also created the character of a floppy white dog with a red nose. In 1999, Nara departed from his typical mediums of painting and sculpture, writing and illustrating his first children’s book titled The Lonesome Puppy.

With the publication of The Lonesome Puppy Nara hoped to engage children, a different audience from the teenagers and adults who are usually fans of his work. Whereas Nara’s subversive paintings and sculptures evoke feelings of bittersweet nostalgia and melancholy in adults, a children’s book written with children in mind conjures up a whole different perspective. While one is retrospective and asks the audience to recall their own possibly lonely youth, the other looks idealistically toward the future and gives children encouragement to cope with and, perhaps, eventually transcend their loneliness. This visual essay will provide a historical and biographical background of Nara’s life in order to understand the prevailing themes of his work, as well as attempt to investigate the significance of the children’s book as a mode of artistic expression and communication. I will also provide a formal analysis of several of the pages in the book. Ultimately, I argue that while all of Nara’s mediums (paintings, drawings, sculptures, and picture books) exhibit his empathy toward the viewer, Nara’s The Lonesome Puppy portrays a much more optimistic view of the world in order to encourage a new generation of children that there is hope and that they will not be lonely forever.

In order to fully comprehend the meaning behind Nara’s work, one must first understand the inseparable relationship between memory and identity. Memories, both personal and collective, have undoubtedly been integral in the shaping of his artistic identity. Jacquelyn Sanders asserts that, “The best authors are the best psychologists. They provide, through their writings, deep insight into human nature and, thereby, a powerful tool for better living and growing.”[1] With this in mind, I argue that Nara’s close examination of his own childhood memories and emotions have led to him being able to write a touching and insightful children’s story. These childhood memories, which he drew so heavily from in his later work, were influenced by the post-war moment that he came of age in. Therefore, when analyzing Nara’s work (or the work of any artist, for that matter), one must first understand the important historical circumstances that influenced their conception.

Our story begins with the inception of the concept of Japanese national essence, identity, and sense of pride known as kokutai. The concept of kokutai emerged in the Edo era (1603–1868), stemming from the Kojiki’s and Nihon Shoki’s ancient historical texts. These texts claimed that Japan’s emperor and the imperial lineage are directly descended from Amaterasu Omikami, the sun goddess. The concepts of “national structure” (the emperor system), “national basis” (the divine origin of Japan), and “national character” (traditional Japanese moral code) found in these texts formed Japan’s cultural and political identity for decades to come.[2] Ever since the Meiji Restoration in 1868, when it ended its almost two hundred year isolation from the rest of the world, Japan worked tirelessly, and ultimately successfully, to assert its independence from Western influence, as well as its dominance over other Asian countries. Japan considered itself on par with any of the other Western powers and, therefore, the rightful colonizer of Asia. Although it had become extremely powerful and had gained the coveted status of a world power, Japan feared “not only…being militarily overwhelmed by the West but also…being ideologically, institutionally, and culturally overwhelmed as well.”[3]

However, at the end of the Pacific War, everything changed. After refusing unconditional surrender, on August 6, 1945, an American B-29 bomber Enola Gay dropped the atomic bomb “Little Boy” on the city of Hiroshima. Several days later on August 9, 1945, the Americans leveled Nagasaki with a second atomic bomb called “Fat Man.” On August 15, after significant civilian deaths, Japan finally surrendered to the United States. The long-reigning kokutai concepts of national sovereignty and identity were decimated in Japan’s defeat in the Pacific War. When the formerly godlike Emperor Hirohito (1901-1989) addressed his subjects in defeat on the radio, he was revealed to merely human, a crushing and humiliating revelation regarding the origin of kokutai. In addition, in the aftermath of the war and unconditional surrender, the United States demilitarized, democratized, and occupied the once proud and formidable Japanese Empire.

After years of successful assertion of Japanese power and independence, this was an unparalleled failure for Japan. As a result of the occupation, kokutai morals were no longer taught in schools. Thus, post-war youth who had not grown up with these values, perceived the concept of kokutai to be outdated and found it to be increasingly irrelevant to their lives. According to Robert Jay Lifton’s article “Youth and History: Individual Change in Post-War Japan”

Harmony and obligation within the group life of family, locality, and nation…[were] now felt to be irrelevant, inadequate to the perceived demands of the modern world. Rather than being a source of pride or strength, they often lead to embarrassment and even debilitation…Underneath…is the profound conviction of the young that they can connect nowhere, at least not in a manner they can be inwardly proud of. ‘Society’ is thus envisaged as a gigantic, closed sorting apparatus, within one must be pressed mechanically into a slot, painfully constrained by old patterns, suffocated by new ones.[4]

This bewildering “ideological void” left by the dissolution of kokutai intensified the widening of the generation gap in terms of “general social outlook” between the youth and their parents.[5] Youth growing up at this time were influenced by American independence, yet retained some of their ingrained traditional Japanese values from their parents. The adults of the pre-war generation who still held onto kokutai values exhibited very different points-of-view from the youth growing up in the post-war moment. Stuck between two worlds, Japanese youth struggled to reconcile these contradictory modes of thought. Lifton states that this is indicative of a widening generation gap, and that “the rapid technological change affecting all mankind has created a universally shared sense that the past experience of older generations is an increasingly unreliable guide for young people in their efforts to imagine the future”[6] In other words, Japanese youth in general felt that their parents could not understand them, leading to a growing sense of loneliness.

Nara’s childhood may be interpreted as indicative of the confusing and rapidly changing times. As these shifts in values occurred on a national level, in the rural village of Hirosaki, Yoshitomo Nara was born in 1959 to a working class family. Nara himself notes that, “My generation in Japan came at the cusp of a shift in family structure, from a large family to a nuclear family. The large family consists of grandparents, parents, and their children…My generation grew up in this transitional period.”[7] These shifts in family dynamic are especially important to note when discussing Nara’s (and other Japanese children’s) loneliness. Nara was the youngest of three brothers and, because his brothers were much older than him, he was raised almost as if he were an only child. In addition, his parents were almost always at work contributing to the rapid postwar economic development. Therefore, because his grandparents were not living in his household either, he became one of the so-called “latchkey children” of the post-war period. These children, like the introverted Nara, spent most of his time alone without parental supervision, watching television, listening to music, reading, and drawing. Young Nara also struggled to fit in with his peers and, as a result, dealt with feelings of alienation, isolation, and loneliness. This lack of meaningful relationships in Nara’s childhood reflects yet another shift from traditional Japanese values, this time in terms of parent-child and peer relationships. As Lifton argues

Japanese children are expected to show the desire to amaeru…to depend upon, expect, presume upon, even solicit, another’s love…According to Dr. Takeo Doi, this pattern of amaeru…is basic to individual Japanese society and is carried over into adult life and into all human relationships. Doi argues further that the unsatisfied urge to amaeru is the underlying dynamic of neurosis in Japan. We can also say that the amaeru pattern is the child’s introduction to Japanese group life…the lesson he learns is: you must depend on others and they must take care of you. It is difficult for him to feel independent, or even to separate his own sense of self from those who care for him or have cared for him in the past.[8]

From Lifton’s and Doi’s perspective, Nara did not have his urge to amaeru fulfilled. Instead of being able to depend on his mother or his peers for affection and support, Nara had to learn to depend on himself.

In 1987, Nara received his Bachelor of Fine Arts and Master in Fine Arts degrees from Aichi Prefectural University of Fine Arts and Music. The following year he moved to Germany and studied at the Dusseldorf Kunstakademie until 1993. Nara says of his life in Germany:

For one reason or another, I ended up living in Germany for 12 years. I became literally 'alone' there. It strongly reminded me of the memory of my lonely childhood. I felt the city's (Düsseldorf) cold and darkness, just like my hometown, and the atmosphere there reinforced my tendency to seclude myself from the outer world. It helped me to remember the boy-me's feelings from back in my hometown, too. So I started talking with the 7- or 8-year-old boy-me in Aomori and the 28-year-old current-me in Germany, beyond the time-gap of 20 years, and the thousands of kilometers of distance between the countries. The result of the conversation was so obvious: what I drew changed drastically.[9]

After graduation, he set up a studio in Koln, Germany and began a creative process of “self-questioning” and interpreted his loneliness as his trademark images of little girls.[10] These little girls have bulbous heads, large slanting eyes with accusatory stares, and are always depicted alone on the canvas. They are also often involved in such subversive activities as smoking, drinking, holding knives, and swearing. As we have seen from his interviews, the inspiration for Nara’s works clearly originates from his lonely childhood.

As noted earlier, Nara spent his childhood immersed in his own vivid imagination, incessantly reading, drawing, and playing with his pets. Instead of drawing comfort from another person, Nara found comfort in his books. While many art historians assume that his art is influenced by anime and manga such as Speed Racer, Nara states that his real influences are the works of Western animators like Walt Disney and Warner Brothers, and especially the children’s picture books he read to entertain himself while his parents were away at work.[11] He mentions that Aesop’s Fables, Hans Christian Anderson fairytales, The Little House by Virginia Lee Burton, German picture books, and various Japanese children’s books were his favorites. He says,

I remember a lot of the picture books and music records I devoured in my youth. I was born and grew up in a rural area in Aomori. I didn't have much opportunity to see 'real' works of art….So the visual images I enjoyed the most were picture books. Not manga, especially. You wouldn't read manga with much imagination. You'd read them passively, looking forward only to see what might come next. With picture books, on the other hand, you'd work your imagination a lot more starting from a picture, and little words would suddenly come along with it. The more you look into the picture the more you think and the more your imaginary world expands.[12]

In his children’s book The Lonesome Puppy, Nara tells the tale of a gigantic dog that is extremely lonely and sad because he is too large for people to notice him. Eventually, a little girl notices him and makes the effort to befriend him. In the end, the Lonesome Puppy and the Little Girl come to appreciate each other and forge a strong friendship that transcends their differences. Unlike his fine art, which is subversive, open-ended, and illustrates themes of rebellion and cynicism present in the adult world, his picture book paints a much clearer and more optimistic view of the world. Through the stimulated imagination of the child, Nara’s simple pictures and spare words are imbued with emotion and meaning and come to life.

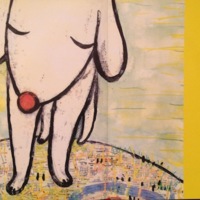

The paintings in the book are executed in Nara’s early style, which has strong black outlines and a sketchy quality to it that is different from his current smooth and well-blended works. At the beginning of the book, the Lonesome Puppy narrates, “I was too big for anyone to notice me, and that is why I was always all alone and lonesome” (Fig. 1).[13]The dog is centered in the middle of a two-page spread, with downcast, closed eyes that make him appear sad, gentle, and even harmless. He towers fantastically above an earth that is composed of a collage of international city maps. The sky around him is a mottled light blue and pale yellow. The Lonesome Puppy’s massive size and loneliness is emphasized by the empty space surrounding him.

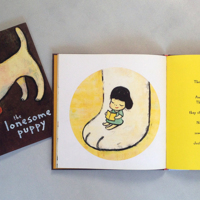

At the end of the book, the narration switches over from the first-person dialogue of the Lonesome Puppy to Nara himself. Nara gives valuable and heartfelt advice from the spirit of his own childhood, saying, “The little girl and the big puppy each found a friend. And they were friends forever. Though sometimes they fought, as friends do, they still had fun and played together. No matter how alone you are, there is always someone, somewhere waiting to meet you. Just look and you will find them” (Fig. 2).[14] The accompanying image is that of the Little Girl in a blue dress leaning against the Lonesome Puppy’s enormous paw and reading a book. The content and peaceful expression on her face is a far cry from the angry and judgmental face she wears in Nara’s regular paintings. The cheerful bright yellow background and the fact that there is more than one person in the image shows that Nara is trying to convey a more lighthearted, innocent, and simple message in this book.

It is interesting to consider Nara’s decision to make a children’s book, especially when put into the context of his childhood. Roberts and Crawford posit that there are two functions of reading: “to forget, to escape from the pressures of daily life and lose themselves within the pages of a story” and “to remember and to take hope, practical support, and a few life lessons from the pages of a book.”[15] Children’s literature should satisfy both purposes. Sanders asks three similar questions in order to determine the quality of children’s books:

First, is the content of interest and importance to the child, so that he knows it is really his? Second, is the content presented in such a way that it is manageable for the child, makes life more manageable and provides models of behavior that are useful and desirable? And, third, are solutions offered in the resolution of the drama, and, if so, are these solutions feasible and constructive?[16]

This is especially relevant for children who are experiencing daily stressors, whether it be parental neglect, bullying from their peers, or feeling misunderstood. In addition to these stressors, parental unemployment, incarceration, divorce, remarriage, and death are some of the especially impactful challenges children may face while growing up.[17] Sanders notes that there is the tendency for adults to try to skirt around difficult topics and issues around children. She compares literature to children using fine china, saying, “Areas of life that are difficult, like china, if avoided will not be understood.”[18] Difficult concepts should not be hidden from children, but should be explained and taught to them so they understand how to work through these problems. The Lonesome Puppy addresses loneliness in a direct, yet compassionate, way. By dealing with the emotional reality of loneliness through the fantastic image of a supersized dog, children can approach their anxieties from a safe distance while simultaneously learning and being entertained. Thus, reading books like The Lonesome Puppy are one way children can escape from these daily anxieties, as well as learn how to cope with their problems, be comforted, and be reassured.

Nara himself escaped into his picture books as a child. The happy ending of The Lonesome Puppy, in which the Lonesome Puppy finds a lifetime friend in the Little Girl, fulfills the function of comfort. Nara’ book gives his young readers hope of finding a friend themselves, despite their possibly less-than-happy current situations. The child may also see himself or herself in either the Lonesome Puppy or the Little Girl. If the child is lonely and without friends, he or she may feel like the Lonesome Puppy. On the other hand, if the child does have friends, he or she might feel encouraged to befriend someone who looks like they do not have many friends.

Thus, I interpret the moral of this story as one of acceptance of one’s differences, tolerance and inclusion of those who may appear a bit different, and hope for the future.

Nara is known for addressing his fans’ inner children in his artwork. However, he had never created work specifically for an actual child before. In the increasingly modern and industrial climate of today, parents still find themselves stuck at work with less time to spend time with their children. The decision to work in the children’s book format may show that Nara is encouraging parents to read to and spend time with their children. Or perhaps the book is meant for lonely children to read on their own to show them that "No matter how alone you are, there is always someone, somewhere, waiting to meet you. Just look and you will find them!"[19] In any case, as the author of this book, Nara seems to take on the role of parent or friend in order to comfort his young reader and to offer them guidance and some sort of amaeru. The fact that Nara lacked this guidance in his own childhood makes his decision even more poignant.

In conclusion, Nara’s lonely post-war childhood influenced his desire to produce a picture book for children similar to those he read as a child. The titular Lonesome Puppy embodies the many emotions of childhood, from sadness and loneliness, to happiness and belonging. Its cute and loveable design is attractive to children, while also reminding adults what it was like to see through the eyes of a child. Unlike his edgier fine art for adults, which aims for a bittersweet and retrospective look at childhood past, children can read his picture book with clear and unsullied hearts. Sanders states that, “what most markedly differentiates [children] from adults is that they are not grown and they are growing. As the child grows, he strives to master both an outer world that is continually expanding and an inner world of emotions that are often tumultuous.”[20] Instead of dwelling on the past, Nara aims to teach the newest generation to transcend their loneliness and to engage with others. Thus, dedicated “to physically challenged children everywhere,” Nara’s children’s book extends understanding, compassion, and guidance to lonely children who feel that they do not quite fit in.[21]

[1] Jacquelyn Sanders, “Psychological Significance of Children’s Literature,” The Library Quarterly Vol. 37, No. 1, Proceedings of the Thirty-First Annual Conference of the Graduate Library School, August 1-3, 1966: A Critical Approach to Children's Literature (Jan., 1967): 22, accessed May 8, 2015, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4305730.

[2] Robert Jay Lifton, “Youth and History: Individual Change in Postwar Japan,” Daedalus Vol. 91, No. 1, Youth: Change and Challenge (1962): 180.

[3] Robert Jay Lifton, “Youth and History: Individual Change in Postwar Japan,” Daedalus Vol. 91, No. 1, Youth: Change and Challenge (1962): 179.

[4] Robert Jay Lifton, “Youth and History: Individual Change in Postwar Japan,” Daedalus Vol. 91, No. 1, Youth: Change and Challenge (1962): 173-74.

[5] Robert Jay Lifton, “Youth and History: Individual Change in Postwar Japan,” Daedalus Vol. 91, No. 1, Youth: Change and Challenge (1962): 178.

[6] Robert Jay Lifton, “Youth and History: Individual Change in Postwar Japan,” Daedalus Vol. 91, No. 1, Youth: Change and Challenge (1962): 181.

[7] Melissa Chiu, A Conversation with the Artist, In Yoshitomo Nara: Nobody’s Fool, (New York: Abrams, 2010), 171-72.

[8] Robert Jay Lifton, “Youth and History: Individual Change in Postwar Japan,” Daedalus Vol. 91, No. 1, Youth: Change and Challenge (1962): 185.

[9] Hideo Furukawa. “An Interview with Yoshitomo Nara,” Asymptote, http://www.asymptotejournal.com/article.php?cat=Interview&id=26 (accessed October 15, 2014).

[10] Shigemi Takahashi, “Miss Spring Waits for the World” in A Bit Like You and Me, (Japan: Foil, 2012), 129.

[11] Kristin Chambers, “Yoshitomo Nara,” MoMA, http://www.moma.org/collection/artist.php?artist_id=25523 (accessed March 26, 2015).

[12] Hideo Furukawa. “An Interview with Yoshitomo Nara,” Asymptote, http://www.asymptotejournal.com/article.php?cat=Interview&id=26 (accessed October 15, 2014).

[13] Yoshitomo Nara, The Lonesome Puppy, (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2008).

[14] Yoshitomo Nara, The Lonesome Puppy, (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2008).

[15] Sherron Killingsworth Roberts and Patricia A. Crawford, “Literature to Help Children Cope with Family Stressors,” Young Children, September 2008, https://www.naeyc.org/files/yc/file/200809/Crawford.pdf, 1.

[16] Jacquelyn Sanders, “Psychological Significance of Children’s Literature,” The Library Quarterly Vol. 37, No. 1, Proceedings of the Thirty-First Annual Conference of the Graduate Library School, August 1-3, 1966: A Critical Approach to Children's Literature (Jan., 1967): 22, accessed May 8, 2015, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4305730.

[17] Sherron Killingsworth Roberts and Patricia A. Crawford, “Literature to Help Children Cope with Family Stressors,” Young Children, September 2008, https://www.naeyc.org/files/yc/file/200809/Crawford.pdf, 1.

[18] Jacquelyn Sanders, “Psychological Significance of Children’s Literature,” The Library Quarterly Vol. 37, No. 1, Proceedings of the Thirty-First Annual Conference of the Graduate Library School, August 1-3, 1966: A Critical Approach to Children's Literature (Jan., 1967): 17, accessed May 8, 2015, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4305730.

[19] Yoshitomo Nara, The Lonesome Puppy, (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2008).

[20] Jacquelyn Sanders, “Psychological Significance of Children’s Literature,” The Library Quarterly Vol. 37, No. 1, Proceedings of the Thirty-First Annual Conference of the Graduate Library School, August 1-3, 1966: A Critical Approach to Children's Literature (Jan., 1967): 15, accessed May 8, 2015, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4305730.

[21] Yoshitomo Nara, The Lonesome Puppy, (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2008).

Bibliography

Besher, Kara. “Yoshitomo Nara.” Assembly Language. http://www.assemblylanguage.com/reviews/nara.html. (Accessed February 5, 2015).

Chambers, Kristin. “Yoshitomo Nara.” MoMA. http://www.moma.org/collection/artist.php?artist_id=25523 (Accessed March 26, 2015).

Chiu, Melissa. A Conversation with the Artist. In Yoshitomo Nara: Nobody’s Fool, 171-183, New York: Abrams, 2010.

Eisler, Ronald. The Fukushima 2011 Disaster. CRC Press, 2012.

Furukawa, Hideo. “An Interview with Yoshitomo Nara.” Asymptote. http://www.asymptotejournal.com/article.php?cat=Interview&id=26. (Accessed October 15, 2014).

Lifton, Robert Jay. Youth and History: Individual Change in Postwar Japan. Daedalus Vol. 91, No. 1, Youth: Change and Challenge (Winter, 1962) (pp. 172-197). October 27, 2014.

Matsui, Midori. “Art for Myself and Others: Yoshitomo Nara’s Popular Imagination.” In Yoshitomo Nara: Nobody’s Fool, 13-25, New York: Abrams, 2010.

Nara, Yoshitomo. The Lonesome Puppy. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2008.

Roberts, Sherron Killingsworth and Patricia A. Crawford. “Literature to Help Children Cope with Family Stressors.” Young Children, September 2008. https://www.naeyc.org/files/yc/file/200809/Crawford.pdf.

Sanders, Jacquelyn. “Psychological Significance of Children’s Literature.” The Library Quarterly Vol.37, No. 1, Proceedings of the Thirty-First Annual Conference of the Graduate Library School, August 1-3, 1966: A Critical Approach to Children's Literature (Jan., 1967): 15-22. Accessed May 8, 2015. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4305730.

Takahashi, Shigemi. “Miss Spring Waits for the World.” In A Bit Like You and Me, 129-131, Japan: Foil, 2012.

Tezuka, Miwako. “Music On My Mind: The Art and Phenomena of Yoshitomo Nara.” In Yoshitomo Nara: Nobody’s Fool, 89-109, New York: Abrams, 2010.

Yasui, Joana. “A Bit Like You and Me: The Creation and Reception of Yoshitomo Nara’s Depictions of Youth in Post-Disaster Japan.” Senior thesis, Bryn Mawr College, 2015.

*Note: Historical background and Nara’s biography draw heavily on my senior thesis research and sources, as cited above.