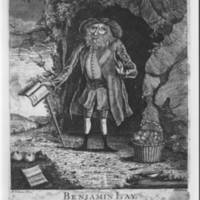

Benjamin Lay

Dublin Core

Title

Subject

Description

ContentDM Collection - Quakers and Slavery

Click Here to View this Document in ContentDM

Click Here to Annotate this Document

Click Here to View Annotations of this Document

Creator

Source

Contributor

Format

Identifier

Writing Assignment Item Type Metadata

Writing Assignment Text

Haverford Identity Critical Response Richard D. Simonds III

From 1832 to 1865, Haverford College faced numerous difficulties, among them its decision to accept non-Quakers into the school. Around 1845, Quaker enrollment in Haverford College declined to 39 students, and the college had tremendous difficulty keeping its finances in order (Bullock 1893, 161). Facing the threat of closing down, the Board of Managers decided to reopen the school opening its doors to non-Quakers (ibid. 165). While this action saved the school from shutting down, many of the board members were against the idea, and some even felt that Haverford College had lost its initial identity (ibid.165, 649). However, others suggested otherwise, stating that the institution’s acceptance of non-Quakers did not prevent it from educating those in the school’s tradition. While some state that Haverford lost its initial identity as a Quaker institution because its exclusivity was one of its defining features, the college was primarily a liberal-arts institution and continued education in the Quaker tradition; therefore, Haverford’s identity did not drastically change. Some may see Haverford’s addition of non-Quaker students as the loss of its initial identity because the original intent of the institution was lost because of needed funds. In the early stages of Haverford’s formation, the Bible Association of Friends desired an institution of higher education out of the fear that Quakers were beginning to not have enough understanding of the Bible and Quaker doctrine (Bullock 1893, 57). As a result, Haverford’s exclusion was central to its early identity of being Quaker, and that the addition of non-Quakers was antithetical to the institution’s early goals. In fact, the original rules for Haverford explicitly states, “the students at this institution shall be Friends, or the children of Friends” and that “the students will be carefully instructed in the fundamental doctrines of Christianity, as held by our religious Society, and in the nature and ground of our Christian testimonies, and their deportment will be required to be consistent therewith” (Friends’ 1832). This document essentially states that Haverford would be a place where Quakers could not only go to receive a higher education but also to learn fundamental values and practices of Quakerism. Therefore, admitting young men not of the Religious Society of Friends would be against the ideological foundations of Haverford College. Even after Haverford admitted non-Quakers out of financial necessity, the Managers stated in 1849 that it hoped for enough students to “create an assurance that admissions may soon again be restricted to members of our religious Society, and to those who shall have been carefully educated in our religious profession” (Bullock 1893, 165). In essence, Haverford’s staff wished for the removal of non-Quakers from the institution even after the school reopened, signifying the high level of hesitance towards the new policy. According to two historians commenting on the nature of Haverford 60 years after its creation, Haverford did not continue to observe one of its founders’ wishes, for “the preservation of morals and the development of spiritual life…to which intellectual matters were held subordinate” (Bullock 1893, 649). In essence, this quote summarizes that Haverford’s loss of its pure Quaker identity led the institution to downplay the religious intentions of its founders. Therefore, many can argue that Haverford lost its Quaker identity as the result letting in non-Quakers. However, Haverford College’s addition of non-Quaker students did not completely change its identity, as it still held steadfast to its liberal-arts focus and maintained teaching in the Quaker tradition. In order to reopen Haverford after its shutdown, the Board of Managers suggested the admission of “the sons of persons who are not members of the religious Society of Friends but are desirous that their children may be educated in the better memories and principles of the Religious Society of Friends” (Suggestion 1846). In essence, the board states that others who would join Haverford not part of Quakerism would still be inculcated with Quaker values and dogma. Since Haverford’s admission of non-Quakers was under the precursor of education of Quaker values, Haverford did not lose its identity. One author writes, “is not this the correct rule of action—that Haverford shall teach Christianity as believed and practiced by Friends, and that all who will may listen? Who can tell how large this audience may become” (Bullock 1893, 165). In essence, he states Haverford’s induction of non-Friends would spread Quaker dogma to non-Quakers; therefore, non-Quakers would not harm the institution nor destroy its Quaker identity. In the initial stages of the formation of Haverford College, several prominent Quaker businessmen wished for “a guarded education in the higher branches of learning, combining the requisite literary instruction with a religious care over the morals and manners of the scholars” (Bullock 1893, 63). In other words, Haverford was founded of the desire to create a haven for higher learning and Quaker teaching; however, this does not specifically state that students have to be Quaker. Haverford contained elements of the liberal arts, therefore, Haverford’s identity was partly separate from its pure-Quaker demographic. Haverford, later mentioned, was “religious but non-theological. Its education was liberal but guarded; its moral teaching strict but charitable” (Bullock 1893, 197). In essence, since Haverford was not too grounded in deep Quakerism, the addition of non-Quakers wouldn’t have drastically changed the institution’s identity. Overall, Haverford’s distancing from steadfast Quaker teaching is why the addition of non-Quakers did not destroy the college’s initial identity. While Haverford’s admission of non-Quakers had a significant impact on the institution, it did not completely change its identity. However, this is not the only period in Haverford’s history in which change altered the College’s image. Whether it would be increasing the student body or admitting women, Haverford would be a place of controversy between those that wanted change and those that did not. And yes, Haverford’s decision to admit non-Quakers was controversial and changing (Bullock 1893, 649). However, in my view, Haverford College still continues to maintain its basic roots through its Quaker Values and Honor Code. Even though only 5% of the Class of 2019 is Quaker, such values and traditions keep the institution as a Quaker School.

Bibliography:

Friends’ Central School, Haverford, 1832, Box 11518, Folder HC09, Haverford College. Board of Managers 1830-03, The Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College Libraries.

Bullock, John G. and Garrett, Phillip C.. A History of Haverford College for the First Sixty Years of its Existence. Haverford, Pennsylvania: Porter & Coates, 1893.

Suggestion to Accept Non-Friends, 1846, Box IA, Folder R1, Minutes of the Board of Managers, 1837-1857, The Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College Libraries.